Kirjakori 2019 statistics (PDF)

Altogether 1255 books for children and youth were collected into Kirjakori of the Institute for Children’s Literature. The number of books was slightly bigger than in 2018, when there were 1190 titles in Kirjakori. According to estimates altogether approx. 1400 books for children and young people were published in 2019, when even the translated graphic novels, of which all are not saved into the collections of the Institute, are included.

The share of national children’s and youth books is over 50 %, already for the third year running. There are altogether 632 national books and 597 translated ones, among the national books 27 Finnish-Swedish books written in Swedish, 13 in Sami language, and 2 in Karelian language.

The children’s and youth literature of the year 2019 deals with several current topics, among them the body of children and adolescent and right of self-determination, school bullying, climate change, and environmental protection. The children’s literature shows also, how the games and hobbies of the children and youth are receiving new spices from technology, yet partly remain the same from decade to decade.

The Finlandia Prize for Children’s and Youth Literature was awarded to Auringon pimeä puoli (WSOY), a youth novel by Marisha Rasi-Koskinen about time travel. The dystopic tale is set in a closed mining town. Among the books of 2019, the nominees for Nordic Council Children and Young People’s Literature Prize are Sorsa Aaltonen ja lentämisen oireet (Otava) by Veera Salmi and Matti Pikkujämsä, as well as Vi är lajon! (Förlaget) by Jens Mattson and Jenny Lucander.

Runeberg Junior Prize was awarded to Katoava muumio (Karisto) written by Tapani Bagge and illustrated by Carlos da Cruz. Arvid Lydecken Prize for meritorious children’s book was awarded to Nelson tiikeritassu (Nelson tigertass, Teos & Förlaget) by Lena Frölander-Ulf. Topelius Prize for praiseworthy youth novel was given to Briitta Hepo-oja’s youth novel Suomea lohikäärmeille (Otava). The Punni Prize of The Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature awarded for the first work or a new opening was given to Eino Nurmisto for his non-fiction book for youth, Homopojan opas(Nemo).

The Finnish Book Art Committee awarded Beautiful Book Prize to Satu Kettunen’s picture book Mörköjuhlat (Tammi); to the children’s poetry book Merimonsterit (Into) by Laura Ruohonen and Erika Kallasmaa; to Silkeapans skratt(Förlaget) by Annika Sandelin and Linda Bondestam; to Anne Vasko’s picture book Lentopusu (Etana editions) for small children; and to the collection of poems Hiiri mittaa maailmaa (Tammi) by Hannele Huovi, illustrated by Elina Warsta. Emmi Jormalainen’s Eksyksissä – Being Lost (Emmi Jormalainen) and Aino Louhi’s Mielikuvitustyttö (Suuri Kurpitsa) are among Beautiful Book Prize award-winning graphic novels in Kirjakori

According to statistics of The Finnish Book Publishers Association there was no significant change in the sale of children’s and youth books when compared with the year 2018. The most sold books among the children’s books were new books by well-known authors, the best-selling was

Hurjan hauska unikirja (Otava) by Mauri Kunnas; Aino Havukainen and Sami Toivonen’s Tatu ja Patu, kauhea Hirviö-hirviö ja muita outoja juttuja (Otava) was the second most sold, and the third Sinikka and Tiina Nopola’s Risto Räppääjä ja ujo Elmeri (Tammi, illustration by Christel Rönns). Jeff Kinney’s children’s and youth book Neropatin päiväkirja 14: Remppaa pukkaa (WSOY; Diary of a wimpy kid, Wrecking ball) was the best-selling translated book.

Categories

Picture books

All in all there are 413 picture books in Kirjakori, of those 164 are national and 249 translated books. Of the translated picture books 97 are so-called toy books: cardboard books intended for very young children.

The protagonists in picture books are mostly children or animals. Children are protagonists in 59 national picture books, animals in 50 books. In translated books, there are 26 child protagonists and 76 animal protagonists. The animals are mostly behaving like human beings. In Kissa Lempisen joulukiemura (Lasten keskus) by Cecilia Heikkinen the protagonist is a cat living in a cardboard box in the alley. The cat ends up in the bookshop of mister Mäyrälä when walking through the town.

The representation of gender of the protagonists in the national picture books is very even, 32 girls and 33 boys. In translated picture books the boys are more often as protagonist (42) than girls (21). In addition 8 protagonists of the national picture books are without specified genre. For example in the book Muttinen ja äiti (WSOY) by Anna Krogerus and Erika Kallasmaa there is a baby called Muttinen, who is not specified as a boy or a girl.

The events of the picture books are usually taking place in everyday surroundings, where the children are adventuring, in addition to their home, in the kindergarten and preschool, in the cities, playgrounds, hospitals, and swimming halls. Often they are in the nature, too. All in all 14 domestic books tell about adventures in the woods, and in addition the children are in the nature e.g. on an island, at sea, on the lake, and in the park.

E.g. in the book Hurja Maija (Karisto), written by Johanna Hulkko and illustrated by Marjo Nygård tells about an ordinary day in the kindergarten. In the book a girl called Maija does not want to dress up as a princess but she wants to be a pirate. More exceptional milieus are in the picture book Karkumatka (Otava) by Inka Nousiainen and Satu Kettunen, in which Pii flees from home into a pension, and Tapani Bagge and Jusa Hämäläinen’s book Pohjoisen pikavuoron arvoitus (Aviador), in which the adventure takes place on a bus.

The picture books are still mostly about nuclear families (26 domestic and 9 translated picture titles). Some singular books introduce single-parents, divorced families or rainbow families. Foster families are presented e.g. in Terhi Kangas and Anna Aalto’s book Helgan ja Helmerin viikonloppuveli (Merkityskirjat), in which the foster child Myrsky comes into the family of Helga and Helmeri, and also in four books of the series Kirahvi Mainion tarinat (Pesäpuu) by Elise Liikala, in which Giraffe Mainio lives as a foster child in an elephant family. The book Nurinkurin Anna (S&S) by Helmi Kekkonen, illustrated by Aino Louhi, tells of a rainbow family, in which the 6-year- old Anna has two mothers.

Children’s books

There are altogether 278 books for children in Kirjakori. More than 60 % of children’s books are domestic: 169 books. 109 books are translations. Of the children’s books more realistic books are published than fantasy books.

Among the fantasy books there is e.g. horror, such as the easy-reader Yökoulu ja vaarallinen operaatio (WSOY) by Paula Noronen ja Kati Närhi, and Anu Holopainen’s Kauhukännykkä (Myllylahti). The last two parts of Karin Erlandsson’s series Ögonstenen: Bergsklättraren, and Segraren (Schildts & Söderströms) are fantasy books. The ordinary everyday is changing into magical realism in Siri Kolu’s book Villitalo (Otava), when Tomtom’s new home takes to its heels and starts walking.

The settings in the realistic books are among others indoor ice rink, school, hairdresser’s, grandmother’s home, and hospital. Jukka-Pekka Palviainen’s book Allu ja kummituskartano (WSOY, illustrated by Christel Rönns) is about a school trip to an old mansion. In Tuula Sandström’s novel for children Tervemenoa sirkukseen! (Enostone, illustrated by Lotta Nevanperä) the children are at grandmother’s home in archipelago in Kustavi and end up into a circus school.

The protagonists of the books for children are mostly children in the national (111) as well as in the translated books (67). Other protagonists are animals and various fantasy characters. There are slightly more girl protagonists than boys.

The majority of families in the children’s books are still nuclear families, but there is some room for a few blended families, single-parent families, and rainbow families. In the illustrated children’s novel Jello ja nolo nokkahuilu (Otava) by Veera Salmi Jello lives alone with his father and is carried away into imaginary adventures, in one of which his father is changed into a tomato.

In 2019 the first part of several translated humoristic series with black-and-white drawings was published. Of series Maailman paras puumaja (Otava, The 13-storey treehouse) by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton two parts were published. The residents of the tree-house, Andy and Terry, are authors, who are threatened by the approaching deadline. Elise Gravel’s Olga ja haiseva olento ulkoavaruudesta (WSOY, Olga and the smelly thing from nowhere) is the first part of series about Olga, who is interested in animals.

Youth novels

There are altogether 176 youth novels in Kirjakori. The amount of national books (100) is slightly more than that of translations (76). Among the translated youth novels approximately same amount of realism as fantasy was published, whereas in national books the amount of realistic books was much more than that of fantasy books.

The protagonist in almost all of the youth novels is an adolescent. There are slightly more girl protagonists than boys in national as well as in translated novels. In the youth novels the family pattern has slightly more variations than in the illustrated books and books for children, but mostly nuclear families are described.

The dystopia has several different variations in the domestic youth novels. Henna Johansdotter’s first novel Glasvaggan(Förlaget) tells about a closed future city, where the cyborg children designed by human architects are hunted. Anders Vacklin and Aki Parhamaa’s Glitch (Tammi) is a sequel to the series Sensored Reality, set in Helsinki of the 2100’s by water surrounded. Nonna Wasiljeff’s Tomupoika (Otava) continues the story of Aaron, who has grown in a closed place called Loukku.

There is more demand for publications of crime novels for young people than published. In Antti Halme’s book Voodookesä (Otava) the young people are adventuring among drug cartels in New Orleans. In Marja-Leena Tiainen’s youth novel Rakas Natasha (Myllylahti) the 18-year-old Joel gets more acquainted with his father just before he dies. After death of his father Joel meets his stepdaughter and finds out that he is unintentionally involved in criminal activities. Hanna Kökkö’s Rocky, Rauha ja rakkaus (Mäkelä) is set in the landscapes of Iittala glass factory. The young people who have just fallen in love get in the middle of a murder investigation. The crime novel Sadie (Karisto) by Courtney Summers, translated into Finnish, takes turns with first-person-narrator Sadie and the podcast of a radio producer solving the disappearance of Sadie.

In many translated youth novels the protagonist is a member of an ethnic group and the whole story is dealing e.g. with matters of identity. Nicola Yoon’s Aurinko on tähti (Tammi, The sun is also a star) tells about Natasha, who is an illegal immigrant from Jamaica. Natasha’s family is facing deportation from the USA. Tahereh Mafi’s novel Rakkaus suurempi kuin meri (Otava, A very large expanse of sea) is about Shirin, who is Muslim and wears the hijab. Shirin’s parents are immigrants from Iran, and the girl feels she is different than the white Americans around her. Tomi Adeyemi’s Veren ja luun lapset (Otava, Children of blood and bone) is the beginning of fantasy series with elements of African mythology, and the main characters of the story are dark-skinned.

Graphic novels

Of graphic novels there are altogether 26 albums, of those 14 are domestic and 12 are translations. The institute adds translated graphic novels only selectively into the collections.

Pauli Kallio and Juliana Hyrri’s Kalle, pallo ja sello (Suuri kurpitsa), and Kalle Hakkola and Mari Ahokoivu’s Sanni & Joonas: metsäretki (Kumiorava), as well as Harri Filppa’s Vastarannan siili: värikäs silta (Soiva Siili) are representatives of the still limited number of domestic graphic novels for children. Of the translated graphic novels for children, two parts of Dav Pilkey’s series Koiramies: Koiramies valloillaan (Dog man unleashed) and Koiramies ja kaksi kissanpentua (Tammi, Dog man:a tale of two kittens) have been published. Eight earlier in magazines Ruutu and Non Stop published stories are collected into Peyo’s album Smurffit (Otava).

Sami Makkonen’s Kalevala (Otava) is a violent and dark graphic novel adaptation of the national epic. Anne Frankin päiväkirja by Ari Folman and David Polonsky is a graphic novel adaptation of the well-known novel describing the life of a young girl in Nazi Germany in 1942–1944. Ellen T (Teos) illustrated by Annukka Mäkijärvi, written by Hanna-Reetta Schreck and Iida Turpeinen, tells about Ellen Thesleff’s life and art. The life of female artists is also described in Reetta Niemensivu’s Maalarisiskot (Suuri kurpitsa).

Poetry

In Kirjakori of the year 2019 there are altogether 40 collections of poems, of which 15 are self-publications of the Books on Demand publishing company, for example Ouch. Papercut, the collection of poems and photos of the 15-year-old Aava Määttä. Also the anthology of poems Voidaan puhua jossitellen (Kosmos) introducing lyrics of 18 young writers and edited by Aura Nurmi, is suitable for young people.

Lorulahja (Lukukeskus), published in the project Lukulahja lapselle, contains poems for children written by 26 Finnish children’s poets. The anthology will be donated to the children born between 2019 and 2021 as a part of Lukulahja lapselle -book bag.

Animals of many kinds are adventuring in the poems by Sinikka Nopola in the book Mustekala löytää trikoot (Tammi). The illustrator of the book is Linda Bondestam. Reetta Niemelä’s poems have extraordinary monsters and fairytale creatures. Kammotuksia-collection (Lasten keskus) is illustrated by Marjo Nygård. Also Mika Myllyneva and Jakke Haapanen’s collection Nurin ja Kurin: pitääkö mandariinisorsa kuoria? (Kustannusosakeyhtiö Kureeri), contains poems tickling the reader’s imagination by playing with funny transformations.

Annika Sandelin’s book Om jag fötts till groda (Förlaget, Finnish translation Jos olisin sammakko, Karisto) tells about dreams of animals, things, and human beings. The illustrator is Karoliina Pertamo. Hannele Huovi’s poems for children from four decades are collected into the anthology illustrated by Elina Warsta: Hiiri mittaa maailmaa: valitut lastenrunot 1979–2019 (Tammi).

Nonfiction

In Kirjakori there are altogether 293 non-fiction books for children and youth, which is more than during any other previous year. 142 domestic non-fiction and 151 translated books were published.

High-quality domestic non-fiction books were published on various topics. Matti Waitinen’s Palovaarin turvaopas(Lasten keskus, illustration Marjo Nygård) tells to children, what to do in case of a fire and what kind of working clothes the firefighters are wearing. Poliisiasema (Tammi) written by Pasi Lönn and illustrated by Jussi Kaakinen introduces the police department and the work of policemen to the readers, under the guidance of police dog Retu.

Karoliina Pertamo’s Lintunaapurini (S&S), a guidebook for a budding birdwatcher, introduces different birds in their own environments. Karkkikirja: makeaa tietoa herkkusuille (WSOY), written by Vuokko Hurme and illustrated by Anni Nykänen, acquaints with various sweets and their history. Karoliina Suoniemi’s Ihan oikeat viikinkiajan lapset(Avain, illustration Emmi Kyytsönen) follows Mielu and Joutsi, children living in Eura during Viking Age. Maria Laakso’s Taltuta klassikko! (Tammi, illustration by Johanna Rojola) guides the young readers in a casual and humoristic way to the classics of literature.

The biographies among others of Greta Thunberg; rap-singer Mercedes Bentso aka Linda-Maria Roine (Venla Pystynen: Mercedes Bentso: ei koira muttei mieskään, Johnny Kniga); rap-artist Mikael Gabriel (Anton Vanha-Majamaa: Mikael Gabriel: alasti, WSOY); and Teemu Pukki (Juha Kanerva: Teemu Pukki: koko tarina (Readme.fi) were published. Hanna Männikkölahti made a plain-language adaption (Avain) of Kari Hotakainen’s book Tuntematon Kimi Räikkönen. Leena Virtanen and Sanna Pelliccioni’s book Ellen! taiteilija Ellen Thesleffin elämä ja villit värit(Teos) is a sequel to Suomen supernaisia -series. In the series Pieni opas suureen elämään of Etana Editions Isabel Thomas’ biographical books Frida Kahlo; Stephen Hawking; and also Danielle Jawando’s book Maya Angelou were published. Malala Yousafzai’s autobiographical novel Meidän oli paettava (Tammi) tells the story of nine refugee girls.

The avalanche of the heroic stories started in 2018 was continued with G. L. Marvel and Leena Parkkinen’s Sankaritarinoita eläimistä, jotka muuttivat maailmaa (Aula & co); Taru Anttonen and Milla Karppinen’s Sankaritarinoita (kaikille) (Into); as well as with Sankaritarinoita pojille (ja kaikille muille) (Into) edited by Emmi Jäkkö and Aleksis Salusjärvi.

Translations

The Kirjakori 2019 -exhibition includes altogether 1229 books for children and youth, if the translations into other languages are here not included. Of these books 632 books or 51 % are domestic. They are written in Finnish or in some other national language.

27 Finnish-Swedish books written in Swedish are included, some of which have also been translated into Finnish. Such is e.g. Fisens liv, collection of poems for children by Malin Klingenberg, illustrated by Sanna Mander (Schildts & Söderströms) and published at the same time in Finnish by the name Pierun elämää (S&S, rhymed into Finnish by Hannele Huovi).

In Karelian language two books were published, for instance the comic book Mecänpeitto by Sanna Hukkanen and Inkeri Aula, translated into Olonets Karelian by Aleksi Ruuskanen (Karjalan kielen seura). There is an exceptionally large amount of children’s books in Sámi language: 13 copies. Included are books published by The Sámi Parliament as well as books published by the Norwegian publishing company Davvi Girji, for example Tove Jansson’s Taikatalvi(Trollvinter) in Inari Sámi language by the name Tijdâtälvi (Sámediggi); and Kirste Palto’s children’s novel Jodašeaddji Násti (Davvi Girji) in Northern Sámi language. During this year nothing has been published in Romani language.

Among the bilingual books there is for example the picture book Ali iyo Hani xaywanka eyjecel yihin = Alin ja Hanin lempieläimet (Kulttuurivoimala – Culture Power Station ry), which is written in Finnish and in Somali. The colourful picture book tells about the everyday life of a Somali family living in Finland. The book is illustrated by Hussein Saleh, and the authors are, along with Mari-Anna Alenius, Shukri Hassan Ali, Luul Hussein Ali, Rahmo Yusuf Hilowle, Hodan Hussein, and Hani Jeelow.

Of translated books 70 % are translated from English. Among the translations from English there is Carmen Saldaña’s funny picture book Krokopardi ja leotiili (Finnish translation Pirkko Talvio-Jaatinen, Nemo), which is tempting the child to combine pop up -animals. A collection of Walt Disney’s nostalgic fairy tales was published in the book Walt Disneyn satumaa (Tammi, Finnish translation by Lea Karvonen, Marjatta Kurenniemi, Sirkka Nuormaa, Outi Nurmi, and Marjatta Soinio). Most of the fairy tales were originally published in the picture book series Tammen kultaiset kirjat during 1953–1974.

The next second most translated books are Swedish (69 books or 6 %). Among other translations from Swedish there is Muumilaakson kertomuksia: Tove Janssonin kirjojen mukaan (Tammi, Finnish translation by Katariina Heilala), written by Alex Haridi and Cecilia Davidsson, illustrated by Cecilia Heikkilä. New versions were published of Gösta Knutsson’s collection of several works, Pekka Töpöhäntä (Gummerus), Finnish translation of which is revised by Turkka Hautala; and new Finnish translations of Astrid Lindgren’s works, as in the previous year. There are also several translations from Norwegian (10 books) and one from Icelandic: Poju – et koskaan lennä yksin, which is based on an international animation and the original idea of Fridrik Erlingsson, written by Styrmir Gudlaugsson, and illustrated by Sigmundur Breidfjörd Thorgeirsson. Janne Kauppila, Arvi-Eemeli Berg, and Ira Carpelan are responsible for the translation into Finnish (WSOY). There are no translations from Danish.

Altogether seven books were translated from Italian language, for example Mortina, written and illustrated by Barbara Cantini, and translated by Katariina Heilala (Tammi). This children’s book, illustrated with coloured pictures, is the first part of series about a zombie girl.

There has been demand for translations from Estonian in the course of years and during last years there’s some nice amount: last year two books, for example Kairi Look’s children’s novel Piia Pikkuleipä muuttaa, illustration by Ulla Saar and translation into Finnish by Katariina Suurpalo (Aviador). From Russian there is Leo Tolstoi’s fairytale collection, originally published in 1892, Luonnosta ja elämästä : satuja ja kertomuksia lapsille, edited by Juri Nummelin and translated by O. H. Moisio (Kustantamo Helmivyö).

There are really few translations from other languages, but something at least: from Portuguese the poetic picture book Kun minä synnyin, text by Isabel Minhós Martins, illustration by Madalena Matoso and Finnish translation by Antero Tiittula (Etana Editions). This picture book was chosen into the exhibition of 100 outstanding picture books at The Frankfurt Book Fair. Kristuksen elämä, Marina Paliaki’s nonfiction book for children (Ortodoksisten nuorten liitto) was translated from Greek. The illustration of the book depicts the icons and wall-paintings of Saint Dionysiu monastery on Mount Athos.

This year 19 books by Finnish authors translated into other languages are included in Kirjakori, and in addition seven books in Torne Valley Finnish. Of Moomin series by Finnish Swede Tove Jansson four new works were translated into Arabic, for example Muumilaakson marraskuu (Sent i november) by the name Wadi al-Mumin fi shahr Tishrin al-thani(Dar Al-Muna). In the exhibition there was among others the French translation of the third book of Janne Kukkonen’s Voro-comics: Voro. Troisième partie, le secret des trois rois (Casterman, translation Kirsi Kinnunen) – there is still lack of the Finnish copy. On the other hand in Estonian Kreetta Onkeli’s children’s novel Poiss, kes kaotas mälu, translated by Ave Leek (Tiritamm) can be read. Among the books in Torne Valley Finnish Ann-Helén Laestadius and Jessica Berglund’s colourful picture book Pimplaus (Lilla Piratförlaget) should be mentioned: the book tells about the winter fishing trip of a family on a lake in northern Sweden. All of the books in Torne Valley Finnish are by Swedish authors.

Themes

Body of child and adolescent

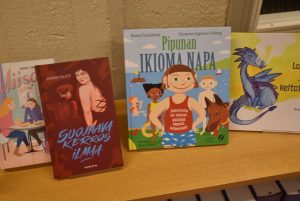

The schools and early childhood education have undertaken the task of teaching safety skills to the children, and this is can also be seen in the children’s literature. The control of one’s body is part of the safety skills. Pipunan ikioma napa(Lasten Keskus), written by Raisa Cacciatore and Susanne Ingman, and illustrated Osmo Penna is a body-positive book in plain-language. At Pipuna’s summer club the members are getting acquainted with their body parts and discussing everybody’s rights to the wonderful body of their own. The own body and its wonderful parts are also admired in Mervi Lindman’s picture book Peppe on ihana (Mäkelä) for the little children.

Lohikäärme, jolla oli keltaiset varpaat (Pieni Karhu), written by Kuura Autere and illustrated by Tina Sarajärvi is a fairytale-like story of the birth of an intersex baby. It is the first Finnish children’s book of this topic. In the end of the book there is a part for grown-ups explaining the physical diversity of intersexuality.

The protagonist in Johanna Hulkko’s youth novel Suojaava kerros ilmaa (Karisto) is 14-year-old Kepa. Kepa is overweight and is suffering from eating disorder. The book tells in detail, what it feels like to be overweight and to see the attitude of other people. Also in Elizabeth Acevedo’s verse novel Runoilija X (Karisto, The poet X) the protagonist is bulky and buxom and has experienced sexual harassment almost daily because of this. Obesity is also one of the themes in Jukka-Pekka Palviainen’s youth novel Opeta minut lentämään (Karisto), in which the friend of a main character going into the upper secondary school specializing in art, tells what kind of teasing the fat young woman has to listen.

Henna Helmi’s Lähes täydellinen Miisa (Tammi) tells about figure skating Miisa, who notices that her costume does not fit on after summer. Miisa is afraid she has been putting on weight and decides to start eating less. After Miisa has been discussing with the grown-ups she understands her body has changed because of the puberty and she understands the meaning of healthy and versatile diet.

Underprivileged, therapy, letters, and empowerment

Mental health and its treatment have become more visible in the literature for young people during the last years. There are more books than before dealing with mental health issues and for example therapy sessions are straightforward described. Jani Pösö and Teemu Niki’s Sekasin (Otava) tells about 17-20-year-old young people who are in the closed unit in the hospital because of mental health problems. The book is based on a TV-series by the same name.

The youth novel Rakas Evan Hansen (WSOY, Dear Evan Hansen) is about a upper secondary school student suffering from anxiety disorder. The therapist tells him to write letters for himself. One of the letters ends up to a classmate, who commits suicide soon after that. Because of the letter Evan gets caught in the tangled web of lies.

Kirjeitä nuorelle itselleni (Docendo) edited by Anneli Juutilainen deals also with letters. The book is a collection of interviews of 21 public figures telling what they would like to say to their younger self. The purpose of the book is to be a source of inspiration and peer support for youth. Peer support is also offered in the anthology Minä jaksan tämän päivän: tarinoita lastensuojelusta (Lastensuojelun keskusliitto) collected by Elina Hirvonen and Juuli Hurskainen. The anthology contains experiences of young people in the beginning of adulthood: how it has been like to live in a family with maltreatment, violence, and other underprivileged circumstances. The young people also write a letter to themselves as a child.

Miia Lehtonen and Minna Jaakkola’s non-fiction book Välikädessä: kirja nuorelle vanhempien erosta (Kasper – Kasvatus- ja perheneuvonta) supplies information to the young of what kind of effect the divorce of the parents has on life, and how to cope with it. The personal experiences of the young people have been collected into the book. Ulrike Falch and Sofie Frøysaa’s Tyttövoimaa! : ensiapupakkaus (WSOY) is an empowering non-fiction book for girls. The book deals among other things with sexism and the inequality and supplies solutions on how to act in difficult situations. The non-fiction book Hetki ennen kuin maailma muuttui (Otava) written by Jenni Pääskysaari and illustrated by Matti Pikkujämsä describes the world changing events and people and encourages the reader to be brave and to change the world in small and big ways.

The picture books for children deal also with underprivileged life. Sorsa Aaltonen ja lentämisen oireet (Otava) written by Veera Salmi and illustrated by Matti Pikkujämsä describes the birds in a breadline, yet tells also, how everybody has bigger dreams and how they have to pursue them. In Tomi Kontio and Elina Warsta’s book Koira nimeltä Kissa tapaa kissan (Teos) a dog lives with a homeless alcoholic Näätä in Helsinki. Even to the outcast a friendship is the most important thing. In Mimmu Tihinen’s novel for children Pieni numero (Karisto) the mother of the primary school-aged Petunia works as a coordinator in the suburb house of a multi-cultured district. Petunia’s father is unemployed and bums coffee from the suburb house. The bullied Petunia edits Pieni numero -newspaper in which she deals with defects she sees.

Environmental responsibility

The climate change and environmental protection is coming up to the fore in several books for children. Laura Ertimo and Mari Ahokoivu’s non-fiction book Ihme ilmat: miksi ilmasto muuttuu (Into) is offering a package of stories to the children about the climate, release, and climate change, and giving explicit answers to many questions on the subject. Näkymätön myrsky (Otava), written by Mikko Pelttari and illustrated by Jenna Kunnas is a story of sisters living in Sumulaakso, who are surprised at the changes in the nature. When the grown-ups are not doing anything, the children start themselves saving the environment.

Two non-fiction books are about the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. Valentina Camerini’s book Gretan tarina: et ole koskaan liian pieni tekemään suuria asioita (Into) is Greta’s biography. Sydämen asioita: perhe ja planeetta kriisissä (Tammi) written by Greta Thunberg and her family tells the changes in the family’s life because of the illness of the children and the climate activism.

In Jenni Erkintalo’s picture book Mato ja meri (Etana editions) a worm sails to the sea in a bottle cap. The worm gets carried away by the adventures and is taking always a larger and larger ship, until the cry for help of the yellow fish because of the pollution of the sea stops the worm. The protection of the Baltic Sea is also dealt with in Loimut (Otava), which is the third book in the youth novel series Synkät vedet by Camilla and Viveca Sten. Tuva, the changeling left by Sea people is examining what the merman wants to signal by sinking a commuter ferry.

Timo Parvela’s Ella ja kaverit hiilijalanjäljillä (Tammi) has three stories concerning environment protection. Marja Aho’s youth novels Puunhalaaja ja Loukuttaja (Atrain&Nord) tell about Unna, who protests the thinning of her beloved forest by using aggressive activism and advocates for the animal rights.

Historical novels and time travel

In children’s as well as in youth literature several novels were published dealing with historical events. The novels were dealing them by way of realism or speculative fiction.

Eva Frantz’ horror story for children Osasto 23 (S&S) is set in Helsinki at the start of the 20th century. The protagonist Stiina suffering from tuberculosis, is given the opportunity to go to the Vadelmarinne sanatorium. The poor family sends the girl into the sanatorium, where nothing is how it looks like. Katoava muumio (Karisto), written by Tapani Bagge and illustrated by Carlos da Cruz continues the series of historical adventure stories. In the third part of the series Apassit a mummy disappears from Ateneum’s exhibition on ancient Egypt.

J. S. Meresmaa’s last book in the Ursine Affairs trilogy of alternative history, Voimanpesä (Robustos) is set in Verla mill village at the end of 19th century. The second sequel in Anniina Mikama’s youth novel series Huijarin oppipoika(WSOY) is set in Cracow of the year 1829.

The youth novel Kunhan ei nukkuvaa puolikuollutta elämää (Tammi) by Raili Mikkanen tells about the life of Minna Canth’s family in Kuopio from the point of view of the second eldest daughter Elli. Reetta Niemensivu’s comics album Maalarisiskot (Suuri Kurpitsa) is describing the life of four art students at the end of the 19th century in Paris. Helene Schjerfbeck, Helena Westermarck, Maria Wiik ja Ada Thilén become aware of the underrating the female students are treated with.

Several books tell about historical and speculative time travels. In Marisha Rasi-Koskinen’s book Auringon pimeä puoli(WSOY) the 16-year-old Emilia winds up travelling in time into her past and living side by side with herself as a child. In Sanna Isto’s youth novel Sirpale (WSOY) the handle of a broken coffee-cup takes the high school student Minja from present to the people who lived in her home during the 1930’s. In Mikko Koiranen’s book Nauhoitettava ennen käyttöä (Myllylahti) the 16-year-old Miro wants to know who is his father. Miro has the chance to meet his young mother over 16 years earlier by the help of an old strange video recorder. Time travel is also dealt with in the children’s novel Tufunus avaruudessa (Teos) by Heikki Lehikoinen; and in Ritva Seppi’s book Susiklaani (Books on Demand), in which the protagonist is able to travel in the guise of wolf into Stone Age. In Cressida Cowell’s Treetooppien kaksosten seikkailut -books Kaksoset ja t-rex and Kaksoset tapaavat Diplodocuksen (Läsrörelsen) the family has ended up into the time of dinosaurs.

School bullying and difference

The picture books are pointing out how being different can lead to bullying. In the picture book Moksu ja Avaruus-Osmo (Minerva), written by Annukka Kiuru and illustrated by Sirkku Linnea the little extraterrestial Osmo is bullied in the space, because it is unlike others. The book Kun kohtaat avaruusolennon: viisi tärkeää ohjetta (Karisto) written by Petri Tamminen and illustrated by Valpuri Kerttula provides instructions on how to meet someone. Even though the passer-by or a new friend would be an extraterrestrial, you have to greet and introduce yourself politely, and then to make sure that the buddy does not have to use the loo.

There are various reasons for bullying. The school bullying is dealt with in Mimmu Tihinen’s book Pieni Numero (Karisto), in which the protagonist Petunia is bullied, because she her clothes are wrong colour, not black but pink. Jaana Levola’s plain-language book Käppänät (Avain) tells about 10-year-old Venla, who has to take some classes in a small group because of reading disorder. Venla is bullied for studying in the small group, but she gets consolation from pet dogs and the reading gets more fluent, when she reads aloud to her grandmother suffering from dementia. In Sam Copeland’s book Sami muuttuu kanaksi (Otava, Charlie changes into a chicken) the 9-year-old Sami is able to flee from bullying by changing into an animal when he gets upset. Tuula Kallioniemi’s Verkot (Otava) is about Sere, who gets transferred into another school in the 6th grade because of bullying. Sere lives with his grandfather and fishing is their common passion. Soon the rumours of Sere’s role of a bully are reaching the new school, too, and he again is summoned to see the teachers.

In Mervi Heikkilä’s fantasy novel Jaan ja jäähammas (Karisto) Jaan is bullied at school, because his father is deceased. Liitopoika (Karisto) by Arja Puikkonen tells about Aku, who was bullied so harshly in the primary school, that he still suffers from nightmares. In the new secondary school the teasing and name-calling goes on. Aku makes friends with two girls interested in hobby horses and he gets acquainted with riding, when he has earlier done leather accessories for horses. In Heidi Silvan’s youth novel Tytti Seckelinin elämä ja esikoisteos (Myllylahti) the writing hobby of the protagonist is found out, when Tytti loses her flash drive and it ends up into wrong hands. Tytti is bullied because of her writing hobby, but later the true reason, jealousy, is revealed.

In the literature for children and young people the auto-fiction has so far not come up in the same way as in the literature for adults. Kirjakori includes some auto-fictional novels for adult, because they are suitable also for YA readers. School bullying is dealt with for example in Antti Rönkä’s novel Jalat ilmassa (Gummerus) based on the author’s own experiences of severe bullying. Traumatic experiences in the young age and feelings of being an outsider is also dealt with in Riina Mattila’s Eloonjäämisoppi (Kosmos). Aino Louhi’s graphic novel Mielikuvitustyttö (Suuri Kurpitsa) tells about the sentiments of a young outsider, too. Also Juliana Hyrri’s graphic short stories of the book Satakieli joka ei laulanut (Suuri kurpitsa) is looking back to the difficult experiences of the childhood.

Games and hobbies

Various games are described in the picture books. Vuokko Hurme and Suvi-Tuuli Junttila’s book Leikkimään, pahvi! (S&S) for little children tells, how many kinds of games are made using cardboard boxes. In Katri Tapola and Karoliina Pertamo’s book Oivan tie (S&S) a motor road is built of clay across the sandbox. Games in the sandbox are also played in Maria Nilsson Thore’s book Kolmikko kaivaa kuopan (Mäkelä). Jemina Heljakka and Pauliina Linjama’s book Pikkupandat leikkipuistossa (Tactic) follows the games of pandas in the park by the help of removable pictures.

Playing with dolls and doll-houses is also told about in Mariko Härkönen’s with photos illustrated book Hansperi rikkoo kaiken (Myllylahti). In the book Elsa ja Lauri riehuvat (Mäkelä) by Kerttu Rahikka and Nadja Sarell the funny games in the daycare are changing into wild running and toy-throwing at home. In Lauri Hirvonen’s book Pei ja Ryhveli pelastajina (Mäkelä) the children are playing rescuers and they design a fire vehicle. Jens Mattson and Jenny Lucander’s picture book Vi är lajon! (Förlaget) tells about two brothers playing savage lions on savannah. The game goes on even though one of the brothers becomes seriously ill.

Heini Junkkaala’s novel for children Kymmenen tikkua laudalla (Otava) gets its name from a familiar outdoor game. In the book Anna is spending summer vacation in the country with her family. She carves ten sticks like in the old game and gives them names of her quarrelsome family members. The sticks start to behave like voodoo dolls.

Kalle Hakkola and Mari Ahokoivu’s comic book Sanni & Joonas: metsäretki (Kumiorava) is a story of plays the siblings are inventing to pass the time during a train trip. Maria Kangaskortet has collected guidelines for hundred easy indoor and outdoor games into her non-fiction book Ruutuvapaata: puuhaa leikki-ikäisille (Otava).

Fanciful games, in which the animals are talking, are described in the book Piia Pikkuleipä muuttaa (Aviador) by Estonian writer Kairi Look. In Vuokko Hurme and Tiina Konttila’s book Eläinhoitola Pehmo ja kiero rakki (WSOY) the sisters are playing kennel in the basement of the apartment building. They get into quarrel, when the ragged toy-dog found by Sisu starts raging. The favoured hobby horse games are included in several books. In Merja and Marvi Jalo’s book Kadonnut raippa (WSOY) the show jumping competition is arranged. The game is discontinued, when the fine riding crop of one of the participants disappears.

In the books meant for older readers the hobby horses are changing from plays into hobbies. Arja Puikkonen’s book Liitopoika (Karisto) describes the hobby horse interest of the upper secondary school aged in which the riding and competitions are accompanied with making horses and equipment and selling them. Virpi Skippari’s non-fiction book Keppihevoset ja keppikrossarit: itse luotuja hevosvoimia (Suomen 4H-liitto) serves as a guide for making the horses.

In the books for older children the games are getting novel forms, for example in Jari Mäkipää’s book Masi Tulppa, klikkien kingi (Tammi). Masi makes a video with his friend Pellervo. The video tells about the adventures of the super hero Hukkajätkä he has made up. But the download of the video into nets has unforeseen results. One of the games frequently dealt with in the books is the detective game, which in the stories often leads to the trails of real criminals. In Joanna Heinonen’s first novel for children Herkko ja kadonneen ajan arvoitus (Myllylahti) the lonesome Herkko plays detective with an animate sheet. The geotrackers get in the middle of detective problems, when they are searching for geocaches in Geoetsivät ja koulun kummitus (Karisto), the tenth book of the series by Johanna Hulkko.

In the verse novel Merikki (Karisto) by Kirsti Kuronen Meri and Ruusu have been best friends from times when they were little. In their childhood they were playing together with Barbie-dolls and later they have written together a plaiting blog. When Ruusu starts seeking the company of new friends, Meri is pondering, how the Barbie-play actually went on.

Linda Skugge’s youth novel Alexia ja teatteripaniikki (Stabenfeldt) describes the youtubing and theatre hobbies of a 13-year-old Alexia. The theatre camp seems to be a disappointment but the performing of a play of her own leads into discussion on Alexia’s father with her mother. Also the 10-year-old Tippi has the theatre hobby in Heidi Silvan’s novel for children Lava kutsuu, Tippi! (Myllylahti). Marja Aho’s Kaikki menee, Jessiina! (Myllylahti) tells about the start for cheerleading. Iiris Suvitie and Marko Laihinen’s youth novel Kymmenestä metristä (Puukenkki) deals with diving.

Football is the hobby for example in Mika Keränen’s novel for children Armando muuttaa Suomeen (Lector); in Mika Wickström’s easy-to-read children’s novel Totti ja saksipotku (WSOY); and Pauli Kallio and Juliana Hyrri’s comics Kalle, pallo ja sello (Suuri Kurpitsa). Kalle is seriously taking an interest in football as well as playing the cello. Uniting the exercise timetables is always not easy. Team sports are brought up in the books by Kalle Veirto, floorball in Takapuolten taisto (Karisto), and ice-hockey in Painajainen kaukalossa (Karisto).

The plain-language book Koiran kanssa (Avain) by Mervi Heikkilä and Marjo Nygård tells about various pet and service dogs. The first books in the series by Riina and Sami Kaarla: Täältä tullaan, lemmikit ja Varkaan jäljillä(Tammi) introduces the animal-lover Kati-e, who helps the animals together with her robot Ti-bot.

Wordplays and significance of books

A full stop can be as a protagonist of a book, too, as in the book Piste (WSOY) by Kaisa Happonen and Joonas Utti. The full stop is fed up with performing at the end of every story and at the end of every sentence. Yet it gets inspired to tell a story of a space dog.

In Anne Vasko’s book for small children Lentopusu (Etana Editions) a book-mobile falls in love with an aeroplane. There is play with characters of different sizes on the pages of the book. Kirsti Kuronen’s picture book Kerro minulle kaunis sana (Karisto) is playing with the meanings of the words in the text and in the pictures by Karoliina Pertamo. There are only ugly words used at home and therefore the child goes away to collect beautiful words. One of the words is received from the librarian, who thinks the most beautiful word is the bookworm.

Fight for the library is going on in the youth novel Henkka & Kivimutka ja Kirjastokarju (Karisto) by Kalle Veirto. The defender of the library is youtuber Kirjastokarju. The second book in Mila Teräs’ fantasy series for children, Kadonnut kaupunki (Otava) an old library book takes the protagonists to the underwater town of Marepolisi.

In Täyden palvelun tarinapuoti (Mäkelä; The one-stop story-shop) written by Tracey Corderoy and illustrated by Tony Neal a brave knight has to look for a new ending for his story at the story shop, because the dragon has gone on vacation. Also the book Tässä kirjassa asuu lohikäärme (WSOY, There’s a dragon in your book) written by Tom Fletcher and illustrated by Greg Abbott is playing with meta-fiction. The reader has to take care that the little dragon living on the pages of the book is not setting it on fire.

Translation: Yrsa Rekola