Kirjakori exhibition showcases Finnish children’s and youth literature from 2018. Altogether 1190 books published in 2018 were collected into Kirjakori. The number of books was slightly smaller than on the year before, in 2017 there were 1257 books in Kirjakori.

The year 2018 can be called a year of strong girls in the children’s and youth literature. On top of numerous stories of strong women, the body and self-determination of girls and the position of women in society are emphasized. Other actual topics, also present in societal discussion, are among other the diversity of gender, attitude towards nature, climate change as well as the effect of various illnesses on the daily life.

Kirjakori 2018 statistics (PDF)

Kirjakori 2018 working group: Heidi Juopperi, Kaisa Laaksonen, Päivi Nordling, Reetta Suomalainen

English translation: Yrsa Rekola

Kirjakori 2018

Altogether 1190 books published in 2018 were collected into Kirjakori of the Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature. The number of books was slightly smaller than on the year before, in 2017 there were 1257 books in Kirjakori. Books were requested from 110 publishers, over 70 % of which donated books to the collections of the institute. According to estimates, altogether near 1400 books for children and young people were published, including graphic novels and books for young adults. The statistics of Kirjakori are based on the donations to the institute.

In 2018 the share of the national literature was for the second consecutive year larger than that of translations, i.e. 52 % of all the published children’s and youth novels were national. The writers and illustrators of fiction books for children and youth are mostly by presumed females. Of the authors of new books 76 % altogether were presumed females in 2018, whereas 24% were presumed males.

The year of 2018 can be called a year of strong girls in the children’s and youth literature. On top of numerous stories of strong women, the body and self-determination of girls and the position of women in society are emphasized. Other actual topics, also present in societal discussion, are among others the diversity of gender, attitude towards nature, climate change as well as the effect of various illnesses on the daily life.

Svenska Barnboksinstitutet pointed out in the Bokprovning report of the year 2018, how influencing and self-determination of children were strongly emerging in Swedish literature for children and youth during last year. Same themes of influencing can be found in Finnish books for children and youth. In Sweden the number of children’s and juvenile books started to decline for the first time since 2010.

The Finlandia Prize for Children’s and Youth Literature was awarded to Tuhatkuolevan kirous written by Siiri Enoranta (WSOY). Enoranta’s youth novel is an individual adventure fantasy, in which the 14-year-old protagonist Pau is invited to the Magia Academy. Runeberg Junior Prize was awarded to Eva Frantz for her first children’s book Hallonbacken (Schildts&Söderströns). This horror story for children takes place in the 1920’s and tells of a girl suffering from tuberculosis, who is sent to the Hallonbacken sanatorium. Arvid Lydecken Prize for meritorious children’s book was awarded to Petja Lähde for Surunsyömä (Karisto), which is about the sorrow of a child. Topelius Prize for praiseworthy youth novel was given to Anniina Mikama’s first novel Taikuri ja taskuvaras (WSOY). Marika Maijala’s Ruusun matka (Etana Editions) and Maria Turtschaninoff’s Breven från Maresi (Förlaget) were the nominees for Nordic Council Children and Young People’s Literature Prize. Comics Finlandia Prize was given to comics anthology Sisaret 1918 (Arktinen Banaani) by 11 authors.

Finnish Book Art Committee awarded Beautiful Book Prize for children’s books to Mirkka Eskonen’s picture book Syksyn salaisuus (Esa Books); Kaisa Happonen and Anne Vasko’s book Mur ja mustikka (Tammi); Marjatta Levanto and Julia Vuori’s book Pelottelun (ja pelon voittamisen) käsikirja (Teos); Marika Maijala’s book Ruusun matka /Etana editions); and Leena Virtanen and Sanna Pelliccioni’s book Minna! Minna Canthin uskomaton elämä ja vaikuttavat teot (Teos).

According to statistics of The Finnish Book Publishers Association the best seller among children’s books in 2018 was Herra Hakkarainen kyläilee (Otava) by Mauri Kunnas. The next most sold ones were Tatu ja Patu, elämä ja teot (Otava) by Aino Havukainen and Sami Toivonen as well as Anne Vasko’s Oma maa mansikka (1. e. 2016, Tammi), which was in the maternity package of 2018. The bestsellers also include new parts to the favourite series, among them Sinikka and Tiina Nopola’s Risto Räppääjä ja juonikas Julia (Tammi), Heinähattu, Vilttitossu ja hupsu enkeli (Tammi) as well as Timo Parvela’s Ella ja kaverit mestarikokkeina (Tammi), and Kepler62 uusi maailma: Kaksi heimoa (WSOY).

Categories

Picture books

Altogether 401 picture books were published in 2018. Among them 156 national and 245 translations. Large amount of picture book authors were presumed females. When it comes to national picture books, 82% of the authors are presumed females and of the illustrators 75%. 71% of translated picture book authors and 62 % of illustrators were presumed females.

In 2018 11 very large picture books and non-fiction books were issued. I.a. Herra Snellman ja makkaran salaisuus (in Swedish Herr Snellman och korvens hemlighet, Snellmanin Lihanjalostus), text by Rami Lehtola and illustration by Sirpa Hammar, of the Frozen-series Seikkailujen valtakunta (Sanoma Media), and Michelle Carslund’s Pienten suuri leikkikirja (Tactic) were published in folio size. Several mini-sized books were integrated into the Christmas calendar book Peppi ja Eemeli (WSOY).

The ones adventuring in the national picture books are mostly children and animals. There were more boys as child protagonists in 2018, altogether 43, whereas the number of girl protagonists was 24. A closer review of the main characters in the picture books of Kirjakori was done in for the first time in 2017, at which time there were far more girl protagonists than boys.

In translated picture books there were 48 boys and 38 girls as protagonists. Main characters include also those personified animals characters, which are clearly featured as girls or boys.

The families in picture books are mostly nuclear families, some books also depict single-parent families. There are no family models of other types, except Sanna Sofia Vuori and Linda Bondestam’s book Ägget (in Finnish Muna, Förlaget/Teos), where many kinds of animal families live in an apartment building. In translated books there are, besides nuclear families, also two blended families and two single-parent families.

The most common site in national picture books is home (21 books) and the daily vicinity such as yard, school, daycare, or playground. The site is more often a city than a countryside. In most books, however, the adventures happen in the woods or nearby nature, at the sea or on an island. In picture books of homeland localities Oulu, Rovaniemi, Tampere, Siikajoki and Syöte are introduced. More particular settings are e.g. submarine, opera house and circus.

Also in translated picture books the adventures take place at home (33 books) and in home environment. Journey destinations include a farm in six books and a construction site also in six books. The translated books take the reader to more exotic places: to the jungle and savannah.

Children’s novels

In the category of children’s books more national books than translated ones were published; of the 245 books for children 161 were national and 84 were translations. The total amount stayed approximately on the same level as in 2017, but the percentage of national once increased slightly.

Among domestic children’s books there were somewhat more realistic books (72) than fantasy (72), especially if the realistic fiction books include those with personified animal characters having adventures in otherwise realistic story (9 books).

The families described in children’s books are mostly nuclear families, but among families also some blended families, single-parent families and sporadic rainbow families in national and also translated books. The protagonists of the children’s books are in most cases children. Other protagonists include animals and various fantasy characters. The number of girl and boy protagonists is rather even, in domestic ones 45 are girls, 37 are boys; in translations 26 girls and 22 boys.

Several children’s novel series from 2017 received the second part. Among the realistic children’s books, Kahden perheen Ebba (Otava) continues Riikka Ala-Harja’s story about Ebba, whose mother lives in Finland and father in Germany. Jari Mäkipää’s book Masi Tulppa rooli päällä (Tammi) tells about Masi’s summer camp. Karin Erlandsson’s fairytale fantasy series’ Legenden om ogönstenen (Taru silmäterästä) second part Fågeltämjaren (Schildts & Söderströms, in Finnish Linnunkesyttäjä, S&S) was published. Vuokko Hurme’s fantasy series Huimaa continued in the book Kaipaus (S&S).

Tove Jansson’s Moomin-books are now all published as new, coherently stylish editions in Finnish (WSOY) as well as in Swedish (Förlaget). WSOY published new translations by Kristiina Rihman of Astrid Lindgren’s books Mestarietsivä Blomqvist, Mestarietsivä Blomqvist vaarassa and Peppi Pitkätossu Etelämerellä.

Youth novels

The total amount of youth novels increased some from the previous year. Altogether 195 copies of youth novels were published, of which 105 were domestic and 90 translations. Among translations there were new editions (in which e.g. new Finnish translation, new illustration or new layout) 32 books, thus there were less new translated than national books for youth. Otava published new editions of Philip Pullman’s trilogy Universumin tomu, when Pullman published the first part of his new trilogy called Vedenpaisumus.

Of the authors of national as well as of translated youth novels 74% are women and 26 % men. Of the main characters in domestic books 44 are girls, 25 boys and two trans-gender; in translated books 33 girls, 12 boys. More commonly supporting characters in the books can be trans-gender or other.

In youth novels the family models are slightly more diverse than in picture books and children’s novels. There are mostly nuclear families in national books as well as in translations, but on top of that also numerous one-parent families and some blended families, rainbow families as well as young people with two homes.

There was a considerably larger amount of realistic books (65) than fantasy books (34) in the national literature for young people, on the other hand somewhat more translated fantasy books (29) than realistic novels (22).

In the youth novels various fantasy worlds are common milieus. The realistic fiction books are often set in urban environments or schools. The events may also take place in real life locations: in Helsinki in at least ten youth novels. In addition, the characters adventure in Hämeenlinna, Raasepori, Lahti, Tampere, Lapland, Kainuu and abroad – among others in the United States, London, Malta and Thailand. The translations take us also to the United States (Chicago, New York, Florida and Texas for instance), to England and Sweden. Milieus in youth novels also include nature and woods, pirate ship, museum, sanatorium, antiquarian, boarding school and senior high school of arts.

When it comes to the topics, the youth literature is closely attached to time and society. Both realistic literature and fantasy are, for example, dealing boldly with diversity of sexes, animal rights, expectations targeted to young people and their possibilities to have an influence over their lives.

Graphic novels

There were altogether 32 graphic novel indexed into the collections, which is slightly more than in 2017. Finnish history and mythology were strongly featured in the national graphic novels. Sanna Hukkanen and Inkeri Aula’s Metsänpeitto (Arktinen banaani) contains nine stories of forest and trees. Mari Ahokoivu’s Oksi (Asema) is based on the bear myth of ancient Finns. 101 sarjakuvaa Suomesta (Zum Teufel) contains one-page strip cartoons, of which each one describes one year of Finnish independency. The winner of Sarjakuva-Finlandia, Sisaret 1918 (Arktinen banaani) tells ten stories of the experiences of women or children during the civil war of 1918. In Pauli Kallio and Pentti Otsamo’s graphic novel Huuhkajia ja Helmareita (Suuri kurpitsa) the stories are describing the history of Football Association in Finland by telling about different levels of tournament of male and female football players, from the point of view of both players and the spectators.

19 translated graphic novels are included in Kirjakori. The library of Finnish Institute For Children’s Literature adds translated graphic novels selectively only into the collection, but from this year on also the first parts of the manga magazines. New manga cartoons are published annually in Finnish. Mae Korvensivu’s Clownfish Twister (Arktinen banaani) starts a new national manga series. In the story Maru changes from boy into girl on his/her birthday.

There are still few graphic novels directed for children. Tiina Konttinen’s nonfiction book Lasten sarjisopas (S&S) shows how to draw cartoons. Patrick Wirbeleit and Uwe Heidschötter’s Loota (Sarjakuvakeskus) tells about Matias and a cardboard box which starts to talk. Dav Pilkey, known of his Captain Underpants books, has in his graphic novel Koiramies (Tammi) a villainous cat Pete as the nemesis of a police, who has a human body and a dog head.

Poetry

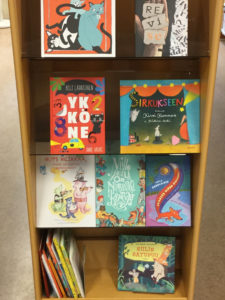

Compared to the previous year, less poetry collections were published, altogether 21, of which 19 national. Elina Pulli’s Sylisampo (Lasten keskus, illustrated by Karoliina Pertamo) contains nonsense rhymes in Kalevala meter. Heli Laaksonen’s Ykköne (WSOY, illustrated by Anne Vasko) uses South-western dialect and plays with numbers.

Tuula Korolainen’s collection Taivasta hipoo hännänpää (Lasten keskus, illustrated by Virpi Talvitie) contains selected poems from years 1990–2018. Kaisa Happonen ja Karri Miettinen’s Revi se! (WSOY) is for young people, prompting them to write collage poetry. The themes of the poems are among others climate change, sexuality and freedom of speech. T.S. Eliot’s Kissojen kielen kompasanakirja (Otava) from year 1939 was now published for the first in Finnish, translated by Jaakko Yli-Juonikas.

Nonfiction

The number of publications of nonfiction for children and young people stayed on the same level as in 2017. A total of 222 nonfiction books were published. There were 119 titles of national nonfiction books, which was the largest amount in the history of Kirjakori reviews.

The domestic nonfiction books are zooming into some sporadic interesting phenomenon or a story of one person. Mitä on punk? (Rosebud ja Suomen Rauhanpuolustajat) by Timo Kalevi Forss and Aiju Salminen describes the background and ideology of punk and introduces punk bands. Pirita Tolvanen’s Paroni Jarno Saarisen elämä (Myllylahti) tells about Jarno Saarinen, the Finnish world champion in motorcycle road race. Carlos da Cruz’ Dinosaurusten mitalla (Teos) is a rare domestic book because of its dinosaur theme. The nonfiction picture book Minne sähkö meni? (Mäkelä) by Tiina Sarja, Mikko Posio and Henna Ryynänen, takes a look into different ways of producing electricity.

Among nonfiction about the lives strong women there was also one nonfiction book for boys about exemplary men: Rohkeiden poikien kirja (Readme)by Ben Brooks.

Easy-to-read and plain language books

Because of the decline in children’s and young people’s literacy and enthusiasm for reading, there is an increasing demand for easy-to-read books. For those learning to read, there are several easy-to-read series published by Mäkelä, such as Sininen banaani, in which a number of translations are published each year. In Kirjatiikeri-series there is, for example, Henriette Wich and Stéffie Becker’s Sankaritarinoita (Mäkelä), which also deals with the matter discussed earlier: child’s bodily integrity and the right to bravely forbid another person to touch it too harshly. Lukupalat-series launched by WSOY a couple years ago received additions, forming sequences inside the series of books. For instance Henna Helmi’s Bellan pennut muuttavat was a new addition to her dog themed novel series. Roope Lipasti’s series about the ice-hockey boy Lauri gained a second part Lätkä-Lauri ja haamupelastus. Karisto started a new colourfully illustrated series for children beginning to read by themselves. In Kirjakärpänen-series Jyri Paretskoi’s Elias ja sukkapallopommipuu and Mila Teräs’ Hotelli Hämärä ja kummituspurkki were published.

For youth, new fun and easy to read literature was published, e.g. Jyri Paretskoi’s K15-series (Otava), of which first two parts K15 and K15 – salaisuuksia were published. Sarah Crossan’s Yksi (S&S) is an easy to read verse novel about Siamese twins.

There is a need for more easy-to-read, illustrated and spaciously folded books, especially for older primary school students and youth.

Books in plain language were published for children and youth, both as plain language novels as well as adaptions of books; for instance plain language adaptions of Marja-Leena Tiainen’s Hiekalle jätetyt muistot (Avain, plain language adaption of book Khao Lakin sydämet) and Timo Parvela’s Maukka ja Väykkä (Avain, adaption by Riikka Tuohimetsä).

Translations

Among the exhibition books of Kirjakori, 52 % or 598 books are of national origin. They are written in Finnish or some other national language. 26 titles are Finnish-Swedish books written in Swedish, some of them also translated into Finnish. In Karelian language, four books were published, for instance Karjalan bukvari: aapinen (Suojärven Pitäjäseura), with text by Matti Jeskanen and team, illustrated by Anni-Julia Tuomisto. In Romani a study book Lokko lamjaha – Kevein askelin (Opetushallitus) by Seija Roth and Tenho Lindström, illustrated by Anita Polkutie was published. The book belongs to the same series as the poetry book carrying the same name published in 2016. Kulje kanssamme: Suomen romanien historia lapsille (Opetushallitus) is a nonfiction book written in Finnish for children about life and culture of Romani people in various moments in history.

Of translated books 71 % are from English. The English classic, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finnin seikkailut received a new translation (translated by Juhani Lindholm, Siltala). Gertrude Stein’s experimental children novel from the year 1939 Maailma on pyöreä was published in Finnish now for the first time (drawings by Anastasia Benzel, translated into Finnish by Tuomas Kilpi, Oppian).

Next most translated are books from Swedish (6%), e.g. new translations of Astrid Lindgren’s books. There are surprisingly many books (11 titles) translated from Norwegian, among them two Julie Andem’s script adaptions of TV series Skam (WSOY), and four picture books of Lars Mæhle’s series Päiväkotidekkari (Tactic). There has been a long wait for translations from Estonian language, and now five were received: humorous stories for children Kun Musti muni mummon, written by Andrus Kivirähk and pictures by the Finnish illustrator Christer Nuutinen (translated into Finnish by Heli Laaksonen, WSOY); Lentokentän lutikat written by Kairi Look, illustration by Kaspar Jancis and Finnish translation by Katariina Suurpalo (Aviador) as well as the nonfiction book for children Mistä on pienet virolaiset tehty? by Kätlin Vainola, illustration by Ulla Saari (translation into Finnish by Heidi Iivari, Viro-instituutti).

There were just a few translations from other languages. From Portuguese there were two books: Sata siementä, jotka lensivät pois by Isabel Minhós Martins and Yara Kono (translated by Antero Tiittula, Etana Editions), and Valaan kertomuksia written by Ana Lucas and illustrated by Ekaterina Dolgova & Anna Polkutie (translated by Antero Tiittula, Into). Picture book Pikkumuurahaisen jännä päivä by Rasa Dmuchovskiene and Gintaras Jocius was translated from the Lithuanian language (from English edition translated by Marianne Kannisto, Minerva Kustannus), and from Russian language into Karelian language L’udmila Mehed’s fairytale book Suarnastu lapsih näh (illustrated by Kira Karenina, translated by Natalia Giloeva, Karjalan kielen seura).

Themes

Girls’ year

The year of 2018 was the year of strong, courageous and rebellious girls in the literature for children and in youth novels. Stories of heroic Finnish women are told in Ida and Riikka Salminen’s book Tarinoita suomalaisista tytöistä jotka muuttivat maailmaa (Teos), Elina Tuomi’s book Itsenäisiä naisia: 70 suomalaista esikuvaa (S&S), and in the book Sankaritarinoita tytöille (ja kaikille muille) (Into) edited by Taru Anttonen and Milla Karppinen. The nonfiction picture book Minna! Minna Canthin uskomaton elämä ja vaikuttavat teot (Teos) by Leena Virtanen and Sanna Pelliccioni is a story of the life and achievements of the great Finnish woman Minna Canth.

Todellisten prinsessojen kirja (Tammi) written by Satu and Johannes Erra and illustrated by Ilona Partanen, awarded in the non-fiction book competition organized by Tammi and Tietokirjallisuuden edistämiskeskus, presents royal women who changed the world in their own era. Princesses are also the subject of Karoliina Suoniemi’s Ihan oikeat prinssit ja prinsessat (Avain) and in the book Prilliga prinsessboken (Schildts & Söderströms, in Finnish Prinsessakirja, S&S) by Sanna Mander and Anna Sarvi, containing information and stories about princesses.

Strong feminist message can be found in the picture book written by Andrea Beaty and illustrated by David Roberts Roosa Ruuti, insinööri (Aula & co), in which Roosa is developing various inventions in her own room. She tries to build an aeroplane for her aunt, and the aunt encourages Roosa with stories of achievements of brave female pilots. Bändin käsikirja (Into) by Hanna Kauppinen, Aiju Salminen and Laura Haarala can also be seen as a power book for women and girls: the book diversely introduces female musicians as well as transgenders and nonbinaries and urges to start a band of your own. Many fretting matters in the life of women are brought up in Emmi Valve’s graphic book Girl gang bang bang: ei kenenkään tyttöjä (Zum Teufel), in which three open-minded young women live together on a wasteland by a circus.

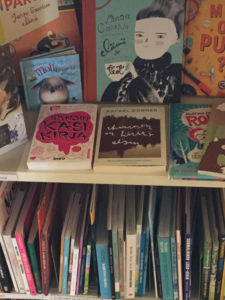

Many titles from picture books to YA novels discuss girls’ bodies and related issues. Ihana Maija (Karisto), written by Johanna Hulkko and illustrated by Marjo Nygård tells of a brave girl in day-care, who ignores being called fat, and just enjoys life as she is. The second part in the Ebba series, Kahden perheen Ebba (Otava) by Riikka Ala-Harja, tells how the 12 years old Ebba gets her first period. The first menstruation is also described in the third part of the book series Väkiveriset: Veden vallassa (Myllylahti) by Sini Helminen. Tuija Takala’s plain language novel Lauralle oikea (Avain) 25-year-old Laura tells of the beginning of menstruation and awakening of the sexuality when she is reminiscing about her youth.

Women’s bodily integrity and the current theme of the voluntary childlessness are brought up in Anu Holopainen’s youth novel Sydänhengitystä (Karisto), in which Tiita, who has just finished the high school, finds out she is pregnant. Tiira immediately decides to have an abortion but gets no support from her family and friends. Bodily integrity is brought up strongly also in Sarah Crossan’s book Yksi (S&S). The main characters of the verse novel are Siamese twins Grace and Tippi, who share the same body down from the hip. In Essi Ihonen’s first novel Ainoa taivas (WSOY) the youngest child of Laestadian family has to mull over the limits set by the religious community and the will of her own when she gets engaged.

In the final part of Maria Turtschaninoff’s Punaisen luostarin kronikat, Breven från Maresi (Förlaget, Finnish translation Maresin voima, Tammi) Maresi returns to her home village and would like to teach the girls to read, but meets resistance. The first two parts of Mervi Heikkilä’s children’s fantasy series Aijalin saaren tarut were published in 2018: Revonpuro and Tuulenkala (Karisto). The protagonist is Pöllö-tyttö. In the second part of the series she moves into town, where the life of women and girls is strictly limited, and they have no right for learning to read. In Holly Bourne’s youth novel Mitä tytön täytyy tehdä (Gummerus) the main character Lottie brings in out her vlog every expressions of sexism she meets during a month. She receives plenty of publicity as well as hate mail. Jennifer Mathieu’s Näpit irti! (Otava) takes place in the 1990’s Texas, where a high school girl protests for the old-fashioned attitude of her school and the harassment of the girls.

In nonfiction books the adolescence of the girls is dealt with in Marawa Ibrahim’s book Tytön oma kirja (Otava) and Lizzie Cox’ Tytön kirja (Tactic) – Cox has written a similar book for the boys, Pojan kirja (Tactic). Pippa Lauka’s Luonnollisesti paras (WSOY) guides girls into good life with advice on diet, appearance pressures and exercise.

Rainbow

The diversity of sex and various family models are regularly apperaing in children’s and YA books. The picture book Ägget (Förlaget, in Finnish Muna, Teos) by Sanna Sofia Vuori and Linda Bondestam describes the neighbourhood of animals. When animal friends are looking for the owner of an egg found in the yard, they meet many kinds of families. The families of two fathers and families of two mothers are normalized and not pointed out; for instance, the main character Raparperi in Johanna Hulkko’s Geoetsivät ja linnavuoden lurjus -book (Karisto) has two fathers and in Nelli Hietala’s novel Kenen joukoissa seisot, Miia Martikainen (Karisto) Miia has two mothers.

The boys’ understanding of their body and sexuality is brought up in Hjärtattack (Förlaget, in Finnish Sydänkohtauksia, Otava), the second part of the series Zoo by Kaj Korkea-aho and Ted Forsström. A friend of Atlas, Miniturkki, starts to exercise and enjoys the company of the exchange student Dharampreet, who is not a girl or a boy, and therefore there’s no need for tension.

Riina Mattila’s first book Järistyksiä (WSOY) tells about Eelia, who at high school age becomes aware of being nor a girl or a boy. In a small locality this is not accepted, but in art school Eelia finally gains confidence. In Meredith Russo’s book Tyttösi sun (Karisto) Amanda has gone through a gender reassignment from male to female, and starts at a new high school when she is 19. The main characters in Magdalena Hai’s fantasy novel Kolmas sisar (Otava) are two young witches, Ciel ja Lune. In the lives of witches love and sexuality are open and multidimensional, and breeding between various genders is possible. Sexual identity and couples of same sex are introduced in Tittamari Marttinen’s book Aurinkoa, Linnea (Karisto). Wolf Kankare’s graphic novel Subdimensionaalinen portti (Suuri kurpitsa) tells of Eelis, who has been bullied in school because of his homosexuality. As a young adult Eelis still dreams about love even if he has been disappointed many times.

Sukupuolena ihminen (Tammi) by Maiju Ristkari, Niina Suni and Vesa Tyni is a nonfiction book, in which ten Finnish transgenders tell about themselves. The book was prized in the series of nonfiction books for young people in the competition organized by Tammi and Tietokirjallisuuden edistämiskeskus. Also Jenni Holma’s Näkymätön sukupuoli: ei-binäärisiä ihmisiä (Voima) tells of transgender people and of those who identify themselves as other.

Spirit and courage

Emotion education is still strongly apparent, especially in the picture books. Ympyräiset -picture book series from year 2017, published by Mäkel,ä continues and introduces new feelings in the books Pomppu Bansku ylikierroksilla, Koala karhu haluaa olla paras, and Puspus pusukala tahtoo leikkiin. In Avril McDonald’s Jukka Hukka -series (PS-kustannus) five books were published dealing with paying attention to other people, getting rid of stress, and surviving grief. There is a part for grown-ups consisting of assignments with tips on how to deal with these themes in a group of children. In the same way Melissa Georgiou’s books in the series Metsäjengi (Breino), published in Finnish, Swedish, and English contain advice for handling these topics with children.

Maija and Anssi Hurme’s Skuggorna (Schildts & Söderström, in Finnish Varjostajat, S&S) describes a child’s sadness, which takes the shape of a shadow and follows the child and the mourning father everywhere. Children’s novel Surunsyömä (Karisto) by Petja Lähde tells about the grief of a father and son after mother’s death. In the book by Katri Kirkkopelto, Molli ja kumma (Lasten keskus) a large creature entering the yard awakens fright and jealousy. Fortunately Molli and Sisu find out that everybody can be courageous in their own way. Mervi Lindman’s picture books Peppe pussaa and Peppe pillastuu (Mäkelä) depict the strong emotions of a small human being.

The children are urged to be brave in the nonfiction book Kuinka minusta tuli rohkea (Otava) by Mervi Juusola and Anni Nykänen. The book there is part story and part informative, about learning the emotional skills and coping with harassment. Kirsi Sjöblom’s Pikkumulperi ja suuret pienet tarinat (PS-kustannus) contains mindfulness-fairytales and exercises meant for children. In Elina Kauppila’s Kamalan ihana päivä: lasten mindfulness (Viisas Elämä) there is a story and information of the conscious presence.

Kirjeitä tuntemattomalle nuorelle (Like) is a part of Yle’s Sekasin-campaign, in which producer Anna-Maria Talvio requested well-known and unknown Finns to write letters for young people. The letters are acting as encouraging examples and can help adolescents to get through their difficulties.

Social phenomena and new Finns

Last year hundred years had passed since the civil war of 1918. Laura Lähteenmäki describes the experiences of five young girls in Tampere during spring 1918 in her youth novel Yksi kevät (WSOY). The girls are at first taking care of young wounded men in a villa conquered from the bourgeois, and when the fights go on they join the female guard. Anneli Kanto’s short story Eväät, in the short story anthology Tusina (Atena), tells about girls in the civil war. In Kalle Veirto’s novel Henkka ja Kivimutka sotapolulla (Karisto) boys have received small roles in a film about the civil war and Hennala’s prison camp. The happenings of 1918 are also dealt with in Sisaret 1918 (Arktinen banaani) -graphic novel.

Sanna Pelliccioni’s Meidän piti lähteä (S&S) is a wordless picture book on refugees’ journey from Middle East to a northern land covered with snow. In Sanna Heinonen’s book Noland (WSOY) two boys playing football become friends, the other having come to Finland as a refugea. He is afraid of the racist violence rising in the small town. In the graphic novel Elias (S&S) by Lauri Ahtinen, the protagonist is a young refugee boy from Afghanistan. He arrived alone and is waiting for the decision for asylum. The picture book Kaksi päätä ja kahdeksan jalkaa (Karisto) by Johanna Venho and Hanneriina Moisseinen tells how difficult it is to write a poem at school, when your native language is not Finnish.

There are persons who have moved to Finland because of various reasons, there are also aptly those in the authors. There are for example: Dinosaurusten mitalla (Teos), a nonfiction book for children by the French-born Carlos da Cruz, who is known of his large-scale productions; How you got your name, a picture book in English (Mökki Galleria) written by British-born Ian Bowie and illustrated by Sibel Kantola, who has her origins in Turkey; and Mimi oppii virheistään and other Metsäjengi-books(Breino) by Australian-born Melissa Georgiou. Rahel Tariku’s The Ethiopian Debre – Depre etiopialainen, written in Finnish and English, tells about Finnish- Ethiopian family. The author is an Ethiopian living in Finland.

Local history and tourism

In 2018 several children’s and juvenile books were tightly attached to a certain setting and time. The first part of the new book series Apassit, Aavehevosen arvoitus (Karisto) by Tapani Bagge and Carlos da Cruz happens in the 1910’s in Helsinki, where a group of children decides to solve the mystery of a ghost horse galloping in the fog. In the second part Vanajaveden hirviö (Karisto), the young detectives have travelled to Hämeenlinna. The set of books abundantly contains references to happenings and persons of the era, such as Jean Sibelius, Rudolf Koivu and Titanic. Also Anniina Mikama’s steampunk youth novel Taikuri ja taskuvaras (WSOY) is set in the past. The 15-year-old orphan Mina tries to survive in Helsinki in the 1890’s by stealing, and she is carried away on an exciting adventure. The opening part of a new books series, Ruusun salaisuus (Tammi) by Martin Widmark and Ola Skogäng has its setting in 1918’s Stockholm. In the story the 12-year- old Stefan lives with his father and ends up solving the reason for his mother’s suicide.

The setting can also be limited to a building, for example. Kristiina Louhi’s picture book series Tomppa continued with Tomppa ja Kerttu-kirjatoukka (Tammi). Tomppa, with his father and little sister Kerttu head for the central library Oodi in Helsinki, and the story introduces its premises and activity. In Arhippa Ristimäki’s book Ylähyllyn kaverukset Uku ja Lele (Kvaliti) the wood goblins have to escape the loggings and construction of terraced houses. They also end up in Helsinki and settle down in cultural centre Stoa in Itäkeskus. Kairi Look’s Lentokentän lutikat (Aviador) the bugs, for their part, decide to clean up their home, ergo the airport, because of the upcoming public sanitation inspection.

The airports and how to act there are often brought up in the picture books as well as in the easy-to-read books. Examples from the year 2018 are Anna-Karin Garhamn’s Ruu lentomatkalla (Otava); Katharina Wieker’s Minidinot matkalla (Mäkelä);Tony Mitton’s Loistava lentomatka (Mäkelä); and also Zanna Davidson’s Sekoilua siivillä (Lasten Keskus). The preparation for trips is also explored in the nonfiction book Lasten matkaopas Eurooppaan (Avain) by Tittamari Marttinen. The book introduces many European cities and their sights from the perspective of travelling with children

Travelling belongs already naturally into the daily life of many children and young people, and this is also visible in the fiction. In Saavu jälleen Roomaan (Enostone), the second part of Silja Pitkänen’s series Mimosa ja Miska, the children adventurein Rome, where their grandfather acts as a guide of the city and its history. Hiekalle jätetyt muistot (Avain) on the other hand is a plain language adaption of Marja-Leena Tiainen’s youth novel Khao Lakin sydämet (Tammi) published in 2013. The 15-year-old Emma returns to Khao Lak in Thailand, where she had lost her family in the disastrous tsunami years ago. There are adventures in Ireland in two books: Merja Jalo’s Jesse aateliskoira (WSOY) and Elina Rouhiainen’s urban fantasy adventure Aistienvartija (Tammi).

Travel around the homeland appears also. Children and young people living in Southern Finland are heading for Lapland in three books. In Tittamari Marttinen’s Aada ja jääkarhu: vauhdikas lumiseikkailu (Mäkelä) the main characters are travelling to Rovaniemi by train. Aada gets acquainted during the train journey with Mimi, who is on a tourist trip with her family from as far as China. Lappilainen: kuolema kahdeksannella luokalla (Karisto) continues L. K. Valmu’s suspense series for young people. Eight-grader Hege heads for Savukoski on his school trip and gets interested in strange deaths there. Sanna Pelliccioni’s picture book series of Onni continues in Onni-pojan talviseikkailu (Minerva), where Onni makes friends with Sami girl Neeta on his trip to Lapland.

Chronic diseases and handicaps as a part of daily life

Disabled or chronically ill children and youth are still rarely main characters in books, but in 2018 some exceptions could be found. In Tuula Kallioniemi’s picture book Neljä muskelisoturia (Karisto) a group of boys is not willing to take Anttu, who has Down syndrome, in their games. When Anttu shows he is as brave as the other boys, they accept him. Heidi Silvan’s youth novel’s John Lennon minussa (Myllylahti) protagonist, the 14-year-old Aija, suffers from Asperger syndrome. In this magic-realistic story Aija keeps pondering if she hears John Lennon’s voice because of her syndrome. Also in Jyri Paretskoi’s series K 15 (Otava) the outspoken Roni has spectrum of symptoms suggesting autism, which leads to bullying at school.

In the plain language book by Mimmu Tihinen, Toivottavasti huomenna sataa (Pieni Karhu), Leo has spent long times in the hospital because of heart disease. Now for the first time in his life he is allowed to go to the countryside. Getting acquainted with Ella from next door feels difficult, because Leo is ashamed to confess he cannot swim or ride a bike. In Heini Saraste’s picture book Pienen koiran onni (Kynnys ry), the owner of a puppy is a cheerful girl, who uses a forearm crutch when standing.

As supporting characters there are more disabled or sick children and young people. In Henna Helmi’s book Tuplapulma, Maria (Tammi) the 9-year-old Maria, who is into synchronized skating, sees how her classmate takes care of her hearing-impaired little sister. In the book Paluu ponikartanoon (Reuna) by Asta Ikonen, the 13-year-old Peppi and her friends teach the blind boy Kaapo how to ride. On the other hand, in Hanna van der Steen’s Senttu ja isosedän haamu (Karisto) Senttu’s friend Maria, who is in the wheelchair, suffers from bullying at school. Senttu wishes that the ghost of her grandfather would help Maria, too. R. J. Palacio’s bestseller Ihme (WSOY) from year 2017 received a companion Auggie & minä (WSOY) in 2018; where we read about three different adolescents, whose lives the severely disabled Auggie touched in various ways. Eeva-Kaisa Suhonen’s nonfiction book Anna ja Elias: mutkikas suoli (Crohn ja Colitis ry) on the other hand tells about the daily life of children suffering from bowel disease.

Organizations and possibilities of influence

A religious or some other type of constricted community can bring safety to the child or adolescent, but it can also limit the life and cause anxiety.

The picture book Villojen kukat (Teos) by Pia Pesonen and Petri Makkonen is about a girl, who moves from Lapland into a block of wooden houses in Helsinki. The force of communality is highlighted when the inhabitants are against the demolition of the houses.

In the youth novel Saari (Otava) by Veera Salmi, children who are abused decide to change the world by establishing a community of their own outside the society. Eventually they discover that isolationism does not solve problems.

The demands of religious communities and trauma caused by experiences connected with them are brought out in Esko-Pekka Tiitinen’s Pikkulinnunrata (Karisto). In Maria Autio’s book Lohikäärmekesä (Karisto) 16-year-old friends end up in a sect called Aurinkopiiri. It becomes clear that the community is not a healing, but practices psychical violence. There is also some criminal activity in the background. The pressures caused by a Laestadian community are described in Essi Ihonen’s debut novel Ainoa taivas (WSOY).

Hannele Mikaela Taivassalo and Catherine Anyago Grünewald’s graphic novel Scandorama (Teos) tells about an idyllic Scandinavian society, in which there is no room for everybody.

The most visible theme in the Swedish literature for children and young people in 2018 was the possibilities of children to influence the society. The chances for influencing and the voices of the children and youth are brought out also in several Finnish books. Jyrki Teeriaho’s Lasten yrittäjäkirja (N-Y-T-NYT) describes the basics of establishing a business in a story. It describes children starting a berry ice-cream enterprise. In the picture book Herra Pupun suklaatehdas (Mäkelä) by Dolan Elys, chickens working in a factory decide to walk out because greedy Mr. Pupu demands them to lay more and more eggs. As a result of the strike the chickens get better working conditions. The third part of the picture nonfiction series by Reetta Niemelä and Sanna Pelliccioni Nähdään majalla, kasviagentit (Sammakko) describes children’s possibilities to have an influence on neighbourhood nature and on the environment. In Kaj Korkea-aho and Ted Forsström’s Hjärtattack (Förlaget, in Finnish Sydänkohtauksia, Otava) Atlas has been chosen into student council and is investigating how he can influence the quality of the school lunch.

Attitude towards nature and animal rights

J-P Koskinen describes in the book Matilda pelastaa maailman (Karisto) a girl who seems to be extremely conscious of her environment, already in her diapers. Matilda’s parents are soon learning everything about recycling and the ecological way of living. Problems with waste and littering are also solved in the book Supermarsu ja roskaavat ryökäleet (Tammi) by Paula Noronen. Martti Lintunen’s plain language picture book Mitä jääkarhu sanoi pingviinille (Pieni karhu) tells about the worryies shared by animals living on the opposite sides of the Earth: the climate change is impairing the living conditions of them both. Valaan kertomuksia (Into), a picture book by Ana Lucas, dwells on the pollution of seas and the living conditions of marine animals. Pelastetaan Itämeri (WSOY) by Iiris Kalliola and Johan Tell is meant for the young people and gives advice on how people can have an effect on the condition of the Baltic Sea.

In the youth novel Beta by Aki Parhamaa and Anders Vacklin the year is 2117 and Helsinki has become a city island surrounded by water. A different kind of dystopia is described in the novel Ikimaa: Soturin tie (Otava) by Kimmo Ohtonen, where people live in a northern country. The wild nature has disappeared and there are only commercial spruce plantations. In Riina and Sami Kaarla’s Arttu Tirttu -books(Lasten keskus) a new student comes into Jim’s class: Eleonora, who lives in a cottage in the woods with her father. She gets Jim acquainted with the ecological lifestyle.

In Antti Nylén’s book Eino ja suuri possukysymys (Otava) Eino’s new talking toy pig challenges Eino to ponder about justification to eat meat. In the youth novel Ailitza (Pääjalkainen) by Elina Koivunen most people are vegetarians. Mere thought of eating meat is horrifying to the 14-year-old protagonist , but she has to mull over the rights of the animals and also plants. Anu Ojala’s Petos (Otava) tells of animal activist Mia, who secretly films cows of an intensive dairy farm.

Sari Mäyränpää’s activity book Petunia Pesukarhun tempputarina has a story of a raccoon, which escapes the persecution of people from Canada to Finland. Proceeds of the book go all to the publisher, Pirkanmaa Humane Society.

Children and youth have hobbies

There is a demand for even more books in amount and variety about hobbies of children and youth. The same sports are represented year by year. Football is played in the easy to read book series Futisjunnut (Otava) by Lasse Anrell as well as in Mika Wickström’s Meidän jengin Zlatan matkalla maineeseen (WSOY), which is the last one in the trilogy. Ice-hockey is on offer as easy to read text in the second part of Lätkä-Lauri-series, Lätkä-Lauri ja haamupelastus (WSOY) by Roope Lipasti (Lukupalat-series), as well as in Kalle Veirto’s youth novel Kyläkaukalon lupaus (Karisto), which is the first one in a new novel series. In Henna Helmi’s book Miisa luisteluleirillä (Tammi) the protagonist is interested in figure-skating, and in the book Tuplapulma, Maria (Tammi) in synchronized skating.

Helmeri Hessunpoika löytää lajinsa (Merkityskirjat) by Terhi Kangas and Anna Aalto is financed by crowdfunding, and the proceeds are used for supporting sport activities of children in low-income families through Pelastakaa Lapset ry (Save the Children Finland). The book describes diversely the possibilities of various sports when the children and adults in Lehmusvirta family are looking for suitable activities. Different sports are also introduced in Reuhurinteen urheilukirjassa (Otava) by Juhana Salakari and Jii Roikonen.

Riding and tending horses are brought up in fiction as well as in nonfiction. Besides horses, there are now also hobbyhorses, which are the subject of nonfiction book Tikkumäen kepparikirja (Otava) by Reetta Niemelä and Salla Savolainen, and the children’s novel Olivia ja Onnentähti (WSOY) by Marvi and Merja Jalo. Tähtikissa (Otava) by Helena Meripaasi tells about interest in dogs and cats. Six-grader Pete takes an interest in agility with his toy poodle in the book Agilitysankarit (Reuna).

Other hobbies described in the children’s and youth books are for example geocaching, e.g in Huojuva torni (Mäkelä) by Hanna Kökkö, and playing in a band in the plain language novel Polttava rakkaus (Avain) by Tapani Bagge. Skeitti-Suomi: rullalautailun tarina (Into) by Sid Sirkia, Tom Elfström, and Ville Heikkala describes skating as a part of youth culture and introduces some devotees. Skateboards are also tried in the picture book Kikattava Kakkiainen ja City-Kanin skeittilauta (Otava).

Rebecca Rissman’s book Joogaa sinulle (Mäkelä) provides information on yoga for youth. Joogaleikki: rohkea leijona ja kepeä perhonen (Nemo), written by Lorena Pajalunga and illustrated by Aanna Láng teaches yoga positions convenient for children. In Fearne Cotton’s picture book Joogavauvat (Mäkelä) even babies are trying yoga.

The extended reality of books

The reality of books sometimes extend outside the pages. There are motion pictures based on children’s and youth books; books are reissued with movie poster covers, and there are books based on films and TV series. E-book versions and audiobooks are increasingly available. Some books are published in virtual versions only. Presently those are not included in the collections of the Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature.

New editions of the books Onneli, Anneli ja nukutuskello (WSOY) by Marjatta Kurenniemi; Puluboin ja Ponin kirja (Otava) by Veera Salmi; and Minä Simon, Homo Sapiens (Otava) by Becky Albertalli were published with movie poster covers. All parts in the Nörtti-series (Otava) by Aleksi Delikouras were published as new editions, when there was a TV-series based on the books. Skam is a popular Norwegian TV-series, of which the scripts of the first and second seasons were published as books in 2018 (WSOY). J. K. Rowling’s Ihmeotukset: Grindelwaldin rikokset (Tammi) -movie script was published also as a book.

Maestro Markus ja Fiktio Fakta (Puukenkki kustannus), a nonfiction picture book by Marko Laihinen, and Markus Rantanen is based on the folk music tour of the authors. In the spring 2018 Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra had a concert based on Timo Parvela’s book Ella konsertissa (Tammi). The book includes a record containing musical pieces composed by Iiro Rantala and performed by the orchestra. Tanhupallo, the winner of sketch character competition in the TV show Putous quickly produced a book of her own, as Kiti Kokkonen’s Tanhupallon askartelukirja (Docendo) was published.

In Ilkka Mattila’s book Neljän rikoksen syksy (Reuna) problems are solved with clues behind QR-codes. Camilla Sandberg’s Sadunhohtoiset keijut (Sandcastle Productions) is published as an audiobook, which operates by QR-codes on the pages. Jari Koiviston’s Miina ja Manu koulutiellä (Satukustannus) was published as an augmented fairytale book, in which the inside becomes extended, when the book is read using an application installed in a mobile device.