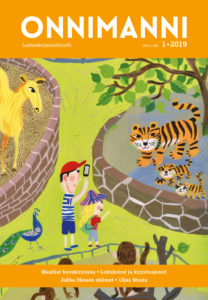

Onnimanni’s current issue focuses on animals in children’s literature. Today’s children are not necessarily in direct contact with wild or farm animal. Instead, they observe animals in zoos and domestic animal yards. Therefore, true-to-life information about real animals in children’s books matters.

The editorial presents a project in Raisio that enabled all second graders in the region to experience farm work and reading aloud to cows. The farm visits increased the children’s knowledge and understanding of the value and rights of animals, as well as the need to treat animals with respect. The visits were also empowering experiences for the children since they reinforced their emotional education.

Mari Taneli has studied how farms and producers are depicted in the latest children’s books. She argues that many translated books for toddlers feature farming and domestic farm animals stuck in an over one-hundred-year-old idyll or otherwise contain false information. Slightly more truthful depictions were found in Finnish picturebooks and non-fiction picturebooks.

Jukka Itkonen’s children’s poems contain exceptionally many animals. In his essay he accounts for common beliefs associated with animals and shares his own animal philosophy. Itkonen accounts for the animals he has encountered in life, of which many have ended up in his poems, songs and stories. He believes that human beings and animals are equally important, and thinks that animals teach humans things that matter, including about inequality.

Päivi Heikkilä-Halttunen presents the latest charismatic animal characters in Finnish children’s books. Many books express a concern for endangered species and climate change. Animals question established truths and practices, as well as take a stand on current issues. In many recent picturebooks, animals interpret the child protagonist’s repressed feelings, such as grief, anxiety and rage.

Pirjo Suvilehto writes about animal assisted therapy and reading dog activities in Oulu. A trained reading dog that has passed an aptitude test listens to children reading out aloud. The dog does not criticise the child for reading too slowly or for making mistakes. The dog’s presence calms the child reader and encourages him/her to keep reading. According to Suvilehto, it is quite normal today to use animals to help young people who struggle with learning to read and write. Reading dog projects were initiated in the USA in 1999 and has awakened interest all over Finland during the past ten years.

Aino Isojärvi has taken a closer look at the British writer Anna Sewell’s novel Black Beauty (1877). Sewell originally wrote the book as a manual how to care for horses. The latest animations of this classic have, however, changed the story into a romantic fairy tale for girls who love horses and riding.

Many new children’s and YA books featuring animals are reviewed in the section Puntari.

Lyly Järvenpää presents Finnish children’s and YA books translated into various languages found in the Institute’s database ”Kolmen tähden tietoa”. Aino-Maria Kangas invites everyone to partake in the Institute’s reading challenge. The column Lukutikku is, after a short break, back with tips for language and literature teaching edited by teacher Juli-Anna Aerila.

Translation Maria Lassén-Seger