Kirjakori 2022 statistics (PDF)

Kirjakori thematic overview (PDF)

Categories

Picture books

Children’s books

Youth books

Books in plain language (Selko)

Poetry

Comics

Non-fiction

Translations and books in different languages

Themes.

The difficult circumstances: COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine

Diversity and multiculturalism

Illness, sensory issues and mental health, abuse and power

Families: babies, divorces and grandparents

Playing with form and language

Princess stories and folk tradition

Growing horror

Forest, nature, and environmental protection

Kirjakori, the annual exhibition of children’s and youth literature in Finland by the Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature, includes 1313 books for children and youth published in 2022. Despite the growing popularity of audio books, the number of printed books has increased from the year 2021, when the number of books was 1222. In 2022 for the first time there was a significant number of works published in audio format only, and these titles are not included in the statistics.

Kirjakori includes printed books for children and youth published in Finland in 2022, both domestic books, and translations. 54 percent of the books are of Finnish origin, meaning there are marginally more domestic books than translations; the ratio has stayed similar in recent years. Some translations of Finnish books to other languages are also included. New editions are included only in the case that they have significant changes from the previous edition, such as new illustrations, cover, or translation.

The book with most copies sold in 2022, similarly to the previous year, according to the statistics from the Finnish Publishers Association, was a children’s book: Kani joka tahtoi nukahtaa by Carl-Johan Forssén Ehrlin (Otava, tr. Ulla Lempinen). Its sales came majorly from audio book sales. In print the best selling domestic children’s book was Pippendorfin kirjavat kummitukset by Mauri Kunnas (Otava), and the translation with most copies sold was Neropatin päiväkirja: Pyhä jysäys by Jeff Kinney (WSOY, tr. Marja Helanen, original The Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Diper Överlöde.)

In the themes of the literature for children and youth, the COVID-19 pandemic that still characterized 2022, and the war in Ukraine were both visible. The main characters in domestic children’s and youth literature are becoming more diverse, which offers chances for identifying with the characters and stories for larger variety of young readers. The main characters may be, for example, People of Colour, disabled, or blind, but at the same time they are allowed to be diverse or different without these features becoming the central theme of the book. Several books deal with themes of sickness, sensory sensitivity, and mental health.

In the depictions of family common themes are expecting a child and parenthood, as well as fights between parents and divorces. In chapter books playing with language is common, whereas in picture books playing with the format and shape of the book is common. Many stories draw from, rework and retell fairy tales, folk traditions and mythologies. Horror books are being published in increasing amounts for both children and youth. Nature, forests, and themes of environmental awareness and preservation are strongly present.

The Finlandia Prize for children’s or youth literature was awarded to Giraffens hjärta är ovanligt stort/Kirahvin sydän on tavattoman suuri, written by Sofia Chanfreau and illustrated by Amanda Chanfreau (Schildts & Söderströms/S&S, tr. Outi Menna). The book follows Vega, who lives on the Island of Giraffes, and sees peculiar animals all around him, that nobody else can see.

Vi ska ju bara cykla förbi/Mehän vaan mennään siitä ohi by Ellen Strömberg (Schildts & Söderströms/S&S tr. Eva Laakso), which was also nominated for Finlandia, was awarded the August Prize, the most notable Swedish award for children’s and youth literature. It became the first Finnish book to ever receive the August Prize.

The Topelius Prize for an outstanding youth book was awarded to Elina Pitkäkangas for her novel Sang (WSOY).

Arvid Lydecken Prize was awarded to Tuomas Marjamäki and Antti Nikunen for their book Nollis: maailman ainoa nollasarvinen (WSOY).

Runeberg Junior Prize was awarded to Roope Lipasti for his historical children’s novel Palavan kaupungin lapset (WSOY), that takes place during the Great Fire of Turku.

Categories

Picture books

There was a slight increase in the number of picture books compared to last year: all in all there are 451 picture books in Kirjakori, 192 of which are domestic and 259 translations. Of the translations 89 are toy books or board books, in domestic books this number is 20.

Many of the picture books depict the everyday life and emotions of children, but they also provide new perspectives on the familiar. For example, in Skelettet/Luuranko by Malin Klingerberg and Maria Sanni (Schildts & Söderströms/S&S, tr. Outi Menna) Teo goes to a party dressed up as a bunny, where seeing his friend’s skeleton costume scares him so badly that he runs away and hurts himself. Teo breaks a bone, which leads to him becoming interested in skeletons, and he understands that there is a skeleton inside every person. In another example, Siri ja kiemurainen kotimatka by Leea Simola (Myllylahti), features two children, whose imagination turn the everyday trip back home from a music class into a jungle adventure.

Här är alla andra/Kaikki toiset by Mimi Åkesson and Linda Bondestam (Förlaget/Etana Editions, tr. Katri Tapola) depicts all kinds of people. For example, the left page of a spread might show people who wear glasses, and the right side people who would need glasses. The book draws attention to the differences between people in a surprising way, which allows the reader to also see that there are also many similarities between us. On the other hand, Alla mina sista / Kaikki löytämäni viimeiset by Maija Hurme (Förlaget / Etana Editions) depicts all kinds of lasts, for example the last diaper, the last one to be chosen into a team, or the last missing piece of a puzzle. Through these different lasts, the book illustrates moments in life, great and small.

Raja by Maria Nilsson Thore (Mäkelä, tr. Raija Rintamäki) is a depiction of boundaries set by adults. There is a red line on the ground of the kindergarten, that the children are not allowed to cross. While all the other children play happily, Nanna cannot stop thinking about the line. What lies beyond it?

In Minttu ja kadonneet kirjat by Maikki Harjanne (Otava), Minttu finds out how important a favourite book is, and has to search for her favourite everywhere. The first Minttu book was published in 1978, and the one published in 2022 became the last one in the series.

A number of silent picture books, which have no text, were published. The silent picture books tell a story through pictures only, which leaves possibilities open for the reader to imagine and make their own interpretations. What is more, they are not dependent on language, so the reader is free to tell the story, in whichever language. Kadoksissa by Kati Närhi (Capuchina) deals with friendship and missing. After losing a friend, it seems as if that friend is everywhere. Kuomaseni by Any-Riikka Lampinen (Enostone) takes the reader through seasons in a forest, where a fox, a bear, and a robin meet each other in watercolor illustrations. Mikkeli Art Museum published the picture book Oletko kuullut järven? by Katriina Kaija, which comes with a soundscape you can access via a QR-code. The illustrations in the book depict a lake through the seasons, showing the fish and animals that live in and by the lake, as well as the people who come to the lake for example to fish. Saari, by Mark Janssen (Kumma) tells a story of surviving a shipwreck. A family’s boat breaks and they find their way to a small island. On the island they see many of the inhabitants of the sea, and the illustrations also show that the island is actually the shell of a giant turtle.

Children’s books

Children’s books include both novels and short stories for children, as well as fairy tales. The total number of children’s books, 349 titles, is the highest in the history of Kirjakori. The statistics have been recorded since 2001. The number of both domestic books (207) and translations (142) has increased from 2021. Most of the children’s books have either black and white, or four colour illustrations. Some of the popular parts in series, that were formerly published with black and white illustrations, have been republished with color illustrations. For example, the first two books in Kapteeni Kalsari series by Dav Pilkey (Tammi, original Captain Underpants) were published with four colour illustrations. Like in previous years, there is a good selection of easy-to-read books for those who are learning to read. In Lukupalat and Kirjakärpänen, WSOY and Karisto’s publisher series featuring domestic books by, sequels were published in series by numerous different authors, for example Neppari ja pupukahvila by Taru Viinikainen (WSOY Lukupalat, ill. Netta Lehtola). There were also new titles in Mäkelä’s publisher series featuring translations. For example, the originally german language book Poni nimeltä Herne by Eva Hierteis (tr. Seija Kallinen, ill. Marc-Alexander Schulze, original Ein Pony namens Erbse) was published in the Kirjatiikeri series, which uses capital letters.

Many of the children’s novels feature super heroes. In Teräsmiespoika ja muita lentäviä asioita by Annastiina Storm (S&S), 10-year old Eevert finds his father’s old pilot hat and decides to practice super hero skills to find his dad. In Ihmetyttö by Sari Peltoniemi (Tammi, ill. Aiju Salminen) everyone in the family of the main character Aili has a superpower, but Aili doesn’t know what hers is yet. The second book in the Superluokka series by Pilke Salo, Kaaos karkeloissa (Karisto, ill. Emmi Jormalainen), features a school class, in which everyone has a superpower.

In När farmor flög/Kun isoäiti lensi by Annika Sandelin (Teos & Förlaget, ill. Jenny Lucander, tr. Veera Antsalo) Joel goes to live with his peculiar grandmother while his parents are on a trip. Soon Joel notices that his grandmother has wings, can fly, and performs heroic deeds. Valo, the main character in Unissa lentämisen opas by Emilia Lehtinen (Avain) dreams about flying. He goes to stay with his aunt Maija while his parents are on vacation, and the aunt teaches him how to fly in his dreams.

Football is featured in many books about hobbies once again. Peli on alkanut, Iida (Karisto), the first book in a new series by Maria Kuutti, follows Iida, who wants to play football, even though there is no team for girls in her hometown. In Pallo on pyöreä, Niki Dundee by Hanna Kökkö (Mäkelä), Niki moves to a new city. The Finnish national team has won bronze in the European Championships, and everyone plays football. Niki has no choice but to join the game.

Two easy-to-read books feature fishing. In Mennään jo pilkille by Maria Kuutti (Kvaliti, ill. Elina Jasu) Ilmari looks forward to an ice-fishing trip with his dad and gets new gear, but dad doesn’t seem to have time to go. In Kalastuspartio Verkkoviikarit by Markku Karpio, which was published in Kirjakärpänen series (Karisto, ill. Anton Lipasti), Oliver, together with his dad and friend, participate in a net fishing competition.

Etsivätoimisto Mysteeri ja ruhtinaan kameleontti (Myllylahti) includes detective tests in the middle of the text, where the reader can solve different puzzles. There are also instructions for creating a room escape game at the end of the book. Heli Koskinen’s first book Zeta: uskallatko pelata (Mäkelä, ill. Mari Luoma), follows Zeta, who spends all their time in the internet playing a game, and gets thrown into a real life adventure because of it.

In Tuukka-Omarille alkaa riittää by Niina Hakalahti (Myllylahti, ill. Jukka Lemmetty), Tuukka-Omar becomes familiar with chickens and caring for them, when his family has to temporarily move to the countryside because of a water damage in their house. The relationship between the children grown up in a city and animals is highlighted, when Tuukka-Omar and his friends wonder where all the other chickens in the world are, because one never sees them.

Pets and talking animals are featured in a remarkable number of books. In Super-someponi Kemppainen by Päivi Lukkarila (Karisto, ill. Milla Paloniemi) Aura’s pony, Kemppainen, can both read and speak, but won’t let anyone else know about his talents. Kemppainen starts making videos for social media, after he hears that affiliate marketing could get him treats. Lemmikkifrendit is a prequel series for the Pet Agents series, which shows how the animal rescue group Pet Agents was formed. There were two books published in this new series by Riina and Sami Kaarla and Anders Vacklin: Bitti ja Moodi, and Moppi (Tammi).

There were three books published in the Koirakamut series by Rachel Wenitsky and David Sidorov: Koirakamut ja täystuho, Koirakamut ja huono turkkipäivä, and Koirakamut ja kutittavat kuteet (Into, ill. Tor Freeman, tr. Sari Kumpulainen). The books depict what happens in a dog daycare and in the dogs’ human families through the eyes of the pet dogs. In Outometsä by Nadia Shireen (Sitruuna, tr. by Maija Heikinheimo), escaping a gang of cats leads a pair of fox siblings from their city home into a strange forest.

Youth books

Note on translation: while young adult books is commonly used in English for the books in this category, for clarity we use youth books here to denote books for the audiences ranging from Middle Grade to the younger end of New Adult. The direct translation of “young adult books”, “nuorten aikuisten kirjat” is closer to what is in English referred to as New Adult literature.

There are 198 youth books in Kirjakori. After a couple of years of decrease, the number of youth books has taken a turn up. There is a notable increase in the number of domestic youth books compared to last year: 118 books, while in 2021 there were only 75. The number of translated youth books has decreased slightly from 90 in 2021 to 80 in 2022. Most of the translations are parts of ongoing series, such as the Norwegian youth thriller series by Jørn Horst Lier (Otava), fantasy books by Rick Riordan, and Maailman viimeiset tyypit series by Max Braillier (WSOY, original The Last Kids on Earth), or Soturikissat by Erin Hunter (Art House, original Warrior Cats).

The target audience for youth books is extensive, from preteens to young adults. Middle grade books that are aimed especially at the preteens in the last years of primary school, can be found placed in both children’s and youth categories. Oma Elämäni by Minna Levola (Karisto) has been categorized by the publisher as a youth book. The main character Linda is on the sixth grade in school, and starts to grow an interest in makeup and boys. Vuokko Vehma. Elämä ja teot by Nelli Hietala (Karisto) follows 13-year old Vuokko, who dresses in colorful clothes and feels like she’s different from the other seventh graders. There are some easy-to-read and illustrated youth books as well, such as Kaksi kuolemaa, monta elämää by Hanna Tähtinen and Marko Laihinen (Puukenkki, ill. Emmi Oksa), and Hännät by Kirsti Kuronen (Karisto, ill. Maria Laakso). The former is an eventful and rough depiction of the lives of young people, which do not go as planned. The latter is a humoristic book about a craze in a secondary school: everyone wants a sewn tail, and soon the tails even make it to the news.

Kaken maailman asiat by Mimmu Tihinen (Uljas & Lucia) consists of “Kakepedia”, a personal encyclopedia written by the main character Kake, where he lists 90 important things from his life. The list format puts together a story where Kake tries to win a chess competition, meets both his biological father and his mother’s ex-partner, and babysits his mother’s current partner’s children.

Many verse novels were published in 2022, for example Kerberos, the final book in the verse novel trilogy by J. S. Meresmaa (Myllylahti); Punapipoinen poika by Hanna van der Steen (Kvaliti); and the first book by Sanni Ylimartimo, Pimeässä hohtavat tähdet (Karisto). The themes of the verse novels are heavy and intense, but the format gives them some lightness. Kerberos deals with for example depression and asexuality acceptance. Pimeässä hohtavat tähdet depicts the feelings of loneliness and not belonging of a girl who likes k-pop, and how finding a fan community helps her. A playful format of the text and verse novel-like narration can also be found in Raakaversio by Ansu Kivekäs (Tammi), where these techniques are used especially in the descriptions of the videos filmed by the main character and when handling heavy themes. A very specific play with the structure and composition of the story can be seen in Pudonneet by Marisha Rasi-Koskinen (WSOY). The book is constructed around a street, through which the fates of three young people are entangled. The stories are built and connected piece by piece through various clues.

The youth novel Naimalupa by Minna Mikkanen (Reuna) portrays the experiences of Jappe on a confirmation camp, where he has to go unwillingly, and where he also has a crush. Ripley: nopea yhteys by Annukka Salama (WSOY) follows Isla, who is a gamer. In the gaming circles she is known as Ripley. She has never met her best friend Damien outside the games.

Maailmantyttäret by Siiri Enonranta (WSOY) is a rare utopia for youth. It takes place in the year 2130, when nature has recovered and there is peace after the world has gone through Great Collapse, an environmental disaster and apocalypse. In the story five teenage girls meet at camp Sopusointu.

For the first time ever, in 2022 content warnings have been added to books published in Finland. In Tuntematon taivas by Elina Rouhiainen (Tammi) the content warnings are at the end of the book, and the list includes for example suicide, war, and violence. There is also contact info for helplines, where one can discuss problems related to these topics. In Rajaton by Tiffany D. Jackson (Karisto, tr. Peikko Pitkänen, original Grown) the content warnings are at the beginning of the book, and they list for example sexual abuse and opioid addiction.

Books in plain language (Selko)

Note on translation: the plain language books can also be called easy-to-read books, but easy-to-read is used of other books as well. The books in this section have been approved by Selkokeskus and been awarded the official easy-to-read status marked by the Selkokirja -logo on the book. For clarity plain language books are used here to denote the books with the official status.

2022 has the highest number of plain language books in the history of Kirjakori, 31 books. There are both plain language adaptations of formerly published books, and original works in plain language. The need for plain language books has increased among readers in all age groups.

There are seven plain language picture books in Kirjakori. These include for example three plain language adaptations of Babar books (Oppian, adapted by Tuomas Kilpi).

In children’s books there are nine plain language titles, for example the adaptation of Supermarsu palaa tulevaisuuteen by Paula Noronen (Oppian, ill. Terese Bast, adapted by Riikka Tuohimetsä).

There are 12 plain language titles in youth literature. The plain language short story collection Aarre: novelleja (Nokkahiiri, ed. Mervi Heikkilä and Kirsi Pehkonen) includes 13 short stories for youth in plain language from various authors. There are both realistic and fantastical stories about the lives of young people in the collection.

Poetry

There are 18 poetry books in Kirjakori, all of which are domestic.

Runorekka by Pia Perkiö (Avain, ill. Pia Sakki) is a collection of poems about various machines and the everyday life at home. Kummalla kammella by Laura Ruohonen (Otava, ill. Erika Kallasmaa) is a nonsense collection about sea travel.

Maailmanpyörässä (Teos) is a collection of poems about differences and similarities. The poems were selected from the submissions for a poetry writing competition held by Teos and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland.

Simpukka by Hannele Huovi (Tammi, ill. Kissa Koskinen) follows a mermaid that falls ill with a deep sadness, but is healed by a magical seashell.

Supersalainen tyttöpäiväkirja by Veera Milja (Tammi) is a poetry book in the form of a diary about the life of a teenage girl in the early 2000s.

Comics

Kirjakori includes 38 comic books and visual novels, 19 domestic and 19 translations. Only a selection of translated comics are taken into the library’s collection, which means that the number does not include every translated comic book that was published in Finland for children and youth.

Comics-Finlandia prize was awarded Kimmo Lust for Silmukka (Suuri Kurpitsa). It is a story of growing up as the only child of a parent that suffers from addiction.

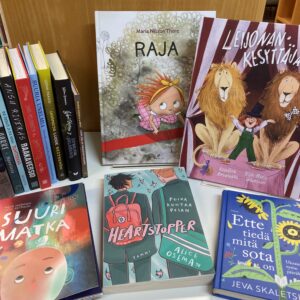

In the youth category, Heartstopper by Alice Oseman (Tammi) can be called the comics phenomenon of the year. The first two books were published in Finnish. The story follows Charlie, as he meets Nick, a rugby player, and the boys get a crush on each other. Nick has to think about his identity, and is somewhat uncertain of what he wants. The popular Netflix series based on the comics was released in Finland at the same time with the books.

Täydellinen Minttu by Maikki Harjanne (Kissanviikset) includes every Minttu comic, that were published in the Kotiliesi magazine between 1982-1990.

Tšernobylin koirat by Johanna Aulén (WSOY) follows the dogs that were left behind in Chernobyl after the nuclear accident, from the time of the accident to this day.

Non-fiction

There are 214 non-fiction books in Kirjakori, 127 domestic and 87 translations. The number stayed about the same as in the previous year.

The themes of domestic non-fiction included for example insects. Myrornas rekordbok/Muurahaisten ennätyskirja written by Katja Bargum and illustrated by Jenny Lucander (Förlaget/Teos & Förlaget, tr. Veera Antsalo), is a non-fiction book about ants. Ants and their behaviour are examined through various records: for example the book presents ants that are the cleanest, strongest, and angriest in the North. Kitisevä koppiskokous by Janina Saari and Anne Muhonen (Minerva) includes a story about beetles that have gathered on an angelica plant, and a fact section about beetles.

Mansikkamysteeri: tarina tiedon etsimisestä by Jukka Laajarinne (Gaudeamus, ill. Mari Luoma) uses a story to explain the basics of scientific research and how to evaluate the reliability of information.

Puhelimen pomoksi: ota digimaailma haltuun by Aino-Maija Tuuri (Tammi, ill. Lille Santanen) is a guide to mastering digital devices and behaving appropriately in the digital environment. Aikamatka: miten telefoonista tuli älykäs by Pinja Meretoja (Tammi) explains the evolution of technology towards the smart phone through the evolutions of various devices, such as camera, radio, television and computer. Tokkerin käsikirja by Jaakob Rissanen and Ville Kormilainen (Otava) is a guidebook to Tiktok, explaining how to use the app and make videos.

Rakennustyömaa by Pasi Lönni and Jussi Kaakinen (Tammi) explains the different stages of building an apartment building. Betonia! by Salla Savolainen (WSOY) shows how concrete is produced.

Translations and books in different languages

Of all translations 71 percent are from English. There are translations from 17 different languages. Perunan kuningaskunta by Helena Koch, translated from Estonian (Kumma, tr. Anja Salokannel), depicts the emotions and wishes of the vegetables in a garden.

Karhujen tasavalta by Juris Zvirgzdins (Paperiporo, ill. Liva Ozola, tr. Mirja Hovila) is translated from Latvian. Bears become targeted by politics, when the minister of strategic planning demands them to be removed from the country. The bears are moved into a reservation, which they start calling the Republic of Bears.

Muovinkalastaja ja muita tulevaisuuden ammatteja by Sofia Rossi and Carlo Canepa (Art House, ill. Luca Poli, tr. Riina Behl) is a translation from Italian. It imagines possible future occupations, such as cloners of the past, solar sailors, and DNA sewers.

The youth novels Maakkanavaran sudet, and Siitavuoren kulta by Mihkkal Marastat (Kieletär Inari, ill. Bjørg Monsen, tr. Katja Anttonen) are translated from Northern Sámi.

This year’s Kirjakori includes 39 books in foreign languages, most of which are translations of books by Finnish creators into other languages.

There are also some multi-language books, and books that were published in Finland in different languages, such as two Ukrainian language compilation books of Ella series, Ella ja kaverit 1 and 2, by Timo Parvela.

Kai menee päiväkotiin by Cat and Dave Cad (Otava, ill. Jenna Kunnas) includes the text in three languages: Finnish, Swedish, and English. The youth novel Stormsommar by Siiri Enoranta was published in Swedish (Förlaget, tr. Mattias Huss).

Themes

The difficult circumstances: COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine

In the beginning of 2022 we were still living with the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, and some restrictions were still in effect. In the 2022 books for children and youth the pandemic is present mostly in references to a past period of time. For example in the short story Majakanvartija, published in the collection Yöuinti ja muita novelleja, by Terhi Rannela (Otava), the main character states that distant learning suited her well. In Virtasten joulut written by Anneli Kanto and illustrated by Noora Kato (Karisto), a family reminisces about the past Christmases, including the one when Santa couldn’t come inside because of the pandemic, and they also couldn’t visit the grandparents.

Varo viruksia, Listamestari, a children’s novel by Tiina Kristoffersson and Vesa-Matti Toivonen (Avain, ill. Olga Pärn) takes place during the COVID-pandemic. Elias’s mother has forbidden him for visiting his friends because of the risk of contagion, and his grandmother won’t let the homecare workers in, because she believes she has caught the virus. In Bertin epätoivopäiväkirja by Sören Olsson and Anders Jacobsson (Avain, tr. Mirka Maukonen, original Berts desperata dagbok) Bert has to be quarantined for two weeks. He is desperate, because he cannot meet his crush Alva. In Myrtti ja kudelmataika by Ursula Mursu (Kumma) a “cough bug” is going around, that spreads easily and people use facial masks to protect themselves from it. The themes of spending time home and the idea of vacationing in your home city, staycation, that followed from travel restrictions, can be seen in the book Manda hemestrar by Tanja Aumanen (Labyrinth books), in which Manda is annoyed because staying home and everything the adults do is boring. However, suddenly exciting things, such as bunnies from television, appear and home starts to seem like a completely new place, where you can have adventures.

The Russian attack in Ukraine in February 2022 and the war in Europe had consequences for the lives of people in Finland as well. There were two children’s books translated from Ukrainian into Finnish. Maja ja ystävät written by Larysa Denysenko and illustrated by Marija Foja (Tammi, tr. Eero Balk) features a fourth grade girl and her friends. The war has had an impact on the life of two of the families. In the footnotes the situation in Ukraine is explained beginning from the Russian attack in eastern Ukraine in 2014. The profits from the book sales goes to the Ukrainian children through Unicef Finland. Ette tiedä mitä sota on by Jeva Skaletska (Otava, tr. Maria Lyytinen) is the diary of a 12-year old girl after the attack in Ukraine. Jeva lives in Harkova, and has to first spend time in a bomb shelter, and later leave the city with her grandmother.

Lappukaulatyttö written by Eppu Nuotio and illustrated by Sanna Pelliccioni (S&S) follows Heidi, who was evacuated from Finland to Sweden during World War II. The book is inspired by real events; the actress Heidi Silja Krohn was evacuated to Sweden twice as a child. Omenarannasta uuteen kotiin written by Lotta-Sofia Saahko and illustrated by Christel Rönns (Tammi) depicts the childhood of Lotta-Sofia’s grandfather in Karelia, and his evacuation. Päivänvarjotyttö written by Katri Tapola and illustrated by Mohammad Sayed Munir (Enostone) is a bilingual picture book, depicting life among war from the perspective of a little girl. The text in the book uses Finnish and Dari.

The youth novel Tuntematon taivas by Elina Rouhiainen (Tammi) takes place during the Second Chechen War in 2002. The book depicts young people, whose lives the war impacts in different ways.

Diversity and multiculturalism

The main characters in children’s and youth literature become perpetually more diverse, featuring characters that more children and young people can identify with. In Lumiyö, a picture book by Sari Airola (Karisto) the main character Lyyti uses crutches. The crutches are never mentioned in the text, they can only be seen in the illustrations. In Maaginen maalipallo by Tuula Kallioniemi (Otava, ill. Jussi Kaakinen) a new kid moves into the neighborhood. Valtteri is blind and goes to a special school. Inspired by Valtteri, FC Wannaplay tries a new sport: goalball.

Elli, the main character of Raakaversio, a youth novel by Ansu Kivekäs (Tammi), has been injured in a car accident. After spending half a year in a hospital she has almost no sensation in her legs, and uses a wheelchair. She is annoyed because she is treated as a disabled youth, who should be content with peer support and talking, while what she really wants is to live a full life like others of her age. Maantiekiitäjä by Reija Kaskiaho (Myllylahti) follows 17-year old Laura, whose life is changed by a fateful dive. Suddenly she is quadriplegic and facing a long rehabilitation process. She used to dream of a career in sports, but is now confined to a wheelchair and cannot even speak at first.

Sang, a youth novel by Elina Pitkäkangas (WSOY), takes place in a future world inspired by Chinese and Tibetan cultures. The main character Dawei, has made a vow of silence, and uses sign language to communicate.

Kielo ja Kaito-kissa (Enostone) by Riina Katajavuori and Hannamari Ruohonen is the third picture book about a girl called Kielo. The illustrations indicate that Kielo has Down’s syndrome, but this is not mentioned in the text.

Differences and limitations can also be approached by using a completely different type of character. In Vuori, joka juoksi, a picture book by Vilja-Tuulia Huotarinen an Anna-Emilia Laitinen (Tammi) the main character is a young mountain, who wonders why mountains cannot run like people, and creates legs for itself.

Non-fiction for youth offers possibilities for connection for young people from different backgrounds. The creators have had experiences of not belonging and exclusion, and want to share their experiences with the youth of today. Tytöille jotka ajattelevat olevansa yksin by Ujuni Ahmed and Elina Hirvonen (WSOY) depicts the experiences of Ahmed growing up in Finland as a girl with immigrant background. The book brings up the difficulties that come from the cultural clash between immigrant families and the Finnish society, and how the children growing up in the middle of the clash do not get support from either their families or the society.

Suuria unelmia: tarinoita suomalaisista, jotka muuttavat maailmaa (Sallado Qasim, Faisa Qasim ja Roosa Oksanen, Books on Demand) tells the stories of 20 Finnish people that belong to minorites. Third Culture Kids (Otava, edited by Mona Eid and Koko Hubara) includes interviews of 40 Finns, who live between cultures. The interviewees examine how they define their own identities, and seek to offer possibilities for connection for those who feel alone.

Nuoren antirasistin käsikirja by Tinashe Williamson (Otava, ill. by Thea Jacobsen, tr. Terhi Width) teaches how to recognize racism and act in antiracist ways. The book is translated from Norwegian, and it includes examples of racism experienced by Norwegian youth.

The short story collection Blackout (Otava, tr. Outi Järvinen) includes short stories written by authors of colour from the United States, the common theme in the stories is a power break in New York.

Illness, sensory issues and mental health, abuse and power

Children’s and youth’s experiences of illness and hospitalization are depicted in three novels. In Tahdon elää, a youth novel by Lilja Kangas (Kustannus Z) the 14-year old main character Taika falls ill. Her frequent headaches turn out to be cancer, and Taika is hospitalized and has to go through a series of difficult and intense treatments. The story depicts the progress of the treatments, and the emotions related to them. Osaston tähti by L. K. Valmu (Karisto) takes place in the New Children’s Hospital in Helsinki. Figure skater Lilja has ulcerative colitis, which requires surgery. In the hospital Lilja makes new friends and thinks about inequality. In Seitsemän kielonlehteä, a fantasy novel by Janne Malinen (Tammi), the main character Oskar falls gravely ill and is sent to a remote Waaralinna sanatorium.

Hypersensitivity and sensory issues are depicted in three picture books. Apua, sukissani on lohikäärmeitä: satuja aistiherkkyydestä by Annika Hämynen and Johanna Lehtomaa (Kumma) follows Kaiku, to whom the voices of others sometimes feel unbearable and it feels as if their socks are full of tickling dragons. The sensory issues are depicted through everyday experiences of Kaiku, and at the end of the book there is an info package about sensory processing and regulating problems.

In Näkymätön reppu, a picture book by Maria Vilja (Karisto) hypersensitivity is depicted as an invisible backpack that Rosali has to carry, that is filled by all the experiences of the day. At the end of the day the backpack may be overfilled, in which case emotions burst out uncontrollably. Kettu ja hiljaisuus written by Reetta Niemelä and illustrated by Eri Shimatsuka (Otava) portrays a fox, whose big ears need silence. The fox searches for silence in a forest, and finally finds some after the other animals understand why the silence is so important for the fox.

In Kaiho-kotitonttu ja rauhaton rantaloma by Emilia Aakko (Kumma, ill. Veera Aro), the house elf Kaiho travels to Rhodos and discovers how hard it is for him to be in a big crowd. The story depicts the need for your own space, and the fear of social situations. In Hundra dagar hemma by Matilda Gyllenberg (Förlaget, ill. Veera Aro), Nike, who is on the fifth grade, cannot go to school because she’s too anxious. Nike finds it hard to explain why school gives her so much anxiety, even though she has a friend there who tries to help her.

The theme of mental health is especially prominent in youth books. In Kerberos, the final installment of a verse novel trilogy by J. S. Meresmaa (Myllylahti), the main character Tuukka has depression. He has started studying geoscience in university, even though sometimes the depression causes him to have black days, when he wants to do nothing but lie in the darkness under the blankets. Punapipoinen poika, a verse novel by Hanna van der Steen (Kvaliti), features Marli, who used to live abroad, but on the ninth grade moves to Finland because of her father’s job. It is difficult for Marli to get used to the wintery Finland. She feels like an outsider, and drunkenly walks on the weak ice. A mysterious boy with a red beanie helps her to go on.

In Nollasummapeli, a youth novel by Heidi Silvan (Myllylahti), the main character Aale is in the last year of high school, and is finding it hard to find motivation to study. Aale goes to therapy, and at the therapist’s he meets a strange Ufo, who starts following him. Aale has been bullied, which is weighing him down, and with the help of Ufo he starts to remember the experiences.

The mental health issues in the youth literature are also connected to power relationships and sexual abuse. Armoton unelma, a youth novel by Riikka Smolander-Slott (Otava) follows Iina, who is a gymnast. Under a strict coach she starts to train too much, and to control her eating to the point where it leads to an eating disorder. The use of power from the coach does not lead to better results in gymnastics, but Iina’s health getting worse.

The pressure to look a certain way and power are featured in Lohikäärmeen kirous, a fantasy novel by Hannele Lampela (Otava). Pentamore, the city of Roses, is ruled by a king that expects everyone to be perfect and to adjust their looks to fit his beauty standards.

In Vi ska ju cykla förbi/Mehän vaan mennään siitä ohi by Ellen Strömberg (Schildts & Söderströms/S&S, tr. Eva Laakso), the friends Malin and Manda live in a small town, but want to experience romances and other exciting things. Malin is having hard time with her father, and suffers from panic attacks. In a party Manda’s crush disrespectfully gropes her, and later also sends a dick pic to her. Manda’s big sister gives him a scolding. She is also able to help Malin with her panic attacks.

In Yökirjaitä by Mila Teräs (Otava), 15-year old Frida has uploaded pictures of herself to social media. An older man takes interest in her, and contacts her. On a visit the man makes Frida drink, and when she’s drunk forces her to have sex with him. At first Frida cannot talk about the experience, and the only way for her to deal with it is to write nightly letters when she cannot sleep. The third installment in the Sekaisin series by Teemu Niki and Jani Pösö, Sekaisin. Tervetuloa Suomeen (Otava) takes place in a reception center for asylum seekers. One of the main characters is a young girl, that a young man working in the center first forces to steal for him, and then rapes.

In Rajaton by Tiffany D. Jackson (Karisto tr. Peikko Pitkänen) Enchanted dreams about a career as a singer. A star singer Kory Fields notices her in an audition, and she becomes a rising star. However, soon Fields turns out to be an abuser, who treats Enchanted terribly, isolates her from the people close to her, manipulates her and drugs her until her memory and mental health start to give up.

In Kaapin nurkista by Eve Lumerto (Nysalor) the main character Jaro is asexual and examines his identity and what it means. Jaro tells his friend Iida about his asexuality, but she kisses and touches him against his will, which makes him very uncomfortable,

Konstaapeli Daniel tässä, moro! by Daniel Kalejaiye (Lasten Keskus) is a non-fiction book for the youth, in which a police officer of social media fame explains criminal activities and the consequences for them. One of the themes is violent and sexual crimes.

Families: babies, divorces and grandparents

Babies and being born are depicted in picture books from the point of view of the parents. In Vauvaskainen by Jani Nieminen and Tuomas Kärkkäinen (Tammi) the main characters are the Future mom and Future dad, who are preparing for the arrival of the baby. From the very moment of birth, Vauvaskainen the baby has a very strong will and it rearranges the lives of the parents completely. In Suuri matka, a zigzag book by Kaisa Happonen and Satu Kettunen (Tammi) the miracle of birth is depicted from the perspective of the baby. In Prinsessa Pikkiriikki ja (kaamea) totuus vauvoista, a picture book by Hannele Lampela and Ninka Reittu (Otava), a baby is growing in the belly of Prinsessa Pikkiriikki’s mother, and Pikkiriikki wants to know how this is possible.

In the books aimed at the youngest audiences the connection between child and parent, and the importance of physical touch are highlighted. Välillä olet varpuseni written by Maaret Kallio and illustrated by Kati Vuorento (WSOY) includes poems that depict different feelings of a baby. Taika-aurinko: piirretään satuja iholle by Nora Lehtinen and Jenni Skyttä-Forssell (Karisto, ill. Reetta Niemensivu) includes short, poem like texts accompanied with instructions for drawing the story on the child’s skin. Maria Kangaskortet has written a bedtime story collection Unitalon tarinoita: nukutussatuja pienille (Otava, Ill. Jonna Markkula). The stories have instructions written in for how the adult can help the child relax and fall asleep with a massage as they read the story. The board book Lorukylpy by Elina Pulli (Lasten keskus, ill. Matti Pikkujämsä) includes nursery rhymes and instructions of how to use them as a part of everyday functions with a baby.

In picture books fathers are strongly present in the lives of children. In Valpuri ja vaarallinen aamupuuro by Saara Kekäläinen and Reetta Niemensivu (Tammi), Valpuri doesn’t want to eat her breakfast. The breakfast is served by her dad, and the other family members are not mentioned or present in the illustrations. Nuku nyt, Viljo by Ylva Karlsson and Erika Kallasmaa (Etana Editions) depicts a father reading a bedtime story to children, and trying to get the little brother Viljo to fall asleep.

Another theme strongly present in the depictions of family in picture books is the disagreements and fights between parents. In Yksisarvinen by Ilja Karsikas (S&S) Moa’s father chases a unicorn, which stands for drinking and partying. His alcoholism causes loud fights between the parents, which Moa tries to solve by emptying dad’s secret drink stash. Leijonankesyttäjä by Katriina Rosavaara and Silja-Maria Wihersaari (WSOY) follows Pipsa, who works as the courageous lion tamer in a circus, and has taken care of the roaring lions ever since she was little. In reality Pipsa is scared of the adults having loud fights, and the voice of the lion tamer doesn’t seem to be heard over the voices of fighting parents.

Divorce has become a prominent theme in children’s books once again. Anna ja eron tuomat muutokset by Noora Alanen (Pieni Karhu, ill. Anne Muhonen) depicts the life of Anna after her parents have divorced. Her parents live in new separate homes, but Anna misses the time when they were all together. Anna thinks her mother’s new boyfriend is scary, but fortunately her big brother Miro listens to her and understands.

In Sonjan kaksi myssyä by Måns Gahrton and Johan Unenge (Lasten keskus, tr. Marketta Pyysalo) the parents’ divorce comes up in Sonja’s choice of hats. Her dad wants her to use an old beanie her mom has knitted for him, but her mom wants to buy her a new beanie. Sonja finds the differing wishes from her parents to be complicated, and in the end she doesn’t want to use either beanie. Bonussisko ja mustat sukat (Tittamari Marttinen, illustarted by Johanna Ilander, Mäkelä) follows Jusa, who has gotten an extra sister in the family via mom’s new partner. The life with the new sister used to be fun, but now Jusa feels like the sister gets all of the attention.

In Sydäntenmetsästäjät, a children’s novel by Jan Forsström, (Teos, ill. Pauliina Mäkelä) Reetta doesn’t want to listen to her parents when they try to tell her about their plan to divorce. Running from the discussion, she gets sucked into an adventure in a parallel world, where people have their hearts outside their bodies for everyone to see.

In many books, grandparents have an important role in children’s lives. In the picture book Benni och skrivmaskinen by Elin Löf (Schildts & Söderströms), Benni often visits his grand-grandmother, aka fammo, after school. There he finds his grand-grandfather’s old writing machine, which fascinates him. In Ensilumi, a picture book by Mila Teräs and Hannamari Ruohonen (Karisto), Tuisku helps his grandfather sew sequins on a figure skating outfit. Tuisku wonders if his grandfather is a man or a woman, and the grandfather tells him that she has always felt like a woman, but didn’t have the courage to tell anyone else until she was an adult.

Mummojen kirja by Reetta Niemelä and Anne Vasko (S&S) does not concentrate on the relationship between a child and a grandparent, but instead it depicts different days in the lives of grandmothers, including coffee shop visits, a book shop, a demonstration, and a picnic in a stairwell. Mummola: runoja mummoista, vaareista ja lapsista, a poetry collection by Tuula Korolainen (Kirjapaja) includes poems for the shared moments between grandparents and children, and depicts different kinds of grandparents.

Playing with form and language

In the children’s novels playing with language and words is common. In Almus: tännetuloa terve by Mikko Kalajoki (WSOY, ill. Jani Ikonen), a troll named Almus appears at mr. Mattsson’s door. The troll comes from Alamaat (Underlands), and uses very peculiar, but understandable language. A vocabulary for the language of Alamaat is included at the end of the book.

In Isäni on hipsteri, by Toni Kontio (Teos, illustrated by Elina Warsta), Nuutti’s school friend Selma calls his dad a hipster. Nuutti starts to wonder what this unfamiliar word might mean. Word play can also be found in Vahna paha, by Hannu Hirvonen (Sarvet, ill. Johanna Taskinen & Aki Nyyssönen). The book follows mr. Rontti, who is the Badwill Ambassador for the United Villaindoms. In the book familiar words are given new meanings in the language of bad will.

Puluboi, Poni ja Ospanjan yksisarvinen kääpiötulilohikäärme by Veera Salmi (Otava, ill. Emmi Jormalainen) is the eighth installment in the Puluboi series, and like the previous books in the series it also plays with language, fonts, and the letter R, which Puluboi doesn’t want to say. In the book Poni’s parents won’t let her have the pet she wants, which prompts Puluboi to become so angry that a letter R escapes from him.

Ötökkämaan ihmeet by Ville Hytönen (Tammi, ill. Virpi Penna) plays with phonemes and alliteration.

Vakoileva hiiri ja muita hulvattomia sanamuunnoksia by Pauli Hokkanen and Tuomas Eriksson (WSOY, ill. Christer Nuutinen) is a guide to spoonerism-like word plays. It begins with two-word word plays and moves on to longer stories.

Otson syksy eli Yskys nosto by Kirsti Kuronen (Sitruuna, ill. Karoliina Pertamo) plays with the structure of the book. The beginning of the story is actually the end of the story, which advances in reverse chronological order. Things are also topsy-turvy in Ella ja kaverit kansankynttilöinä by Timo Parvinen (Tammi, ill. Anni Nykänen). Ella and her school friends become teachers for a week, when their parents realize how important it is to hear the children’s opinions. Their students are the parents, who find it very hard to, for example, let go of their phones for the duration of the class.

God morgon rymden/Hyvää huomenta avaruus by Linda Bondestam (Förlaget & Berghs/Teos & Förlaget, tr. Päivi Koivisto), follows the morning activities of a child in space, and the entire space. The pages in the book are different sizes and shapes, and have holes and other interesting cuts in them. The shape brings playfulness and a feeling of foreignness into the homes of the aliens.

Dinoja ei ole, a picture book by Mark Janssen (Kumma, tr. Sanna van Leeuwen) follows Lasse and Jesse, who go into a forest in search of dinosaurs. Every other spread in the book has folded pages that can be opened to reveal a double spread. What looks like a small hill under the boys, is revealed as a giant dinosaur, which the boys do not notice.

Kokka kohti aarretta, kapteeni Hirmuliini by Sylvie Misslini and Amandine Piu (Lasten Keskus, tr. Rauna Sirola) is a choose your own story type picture book translated from French. The options are marked with symbols that lead to the right page.

In Kirja joka ei halunnut tulla luetuksi by David Sundin (Tammi, tr. Tittamari Marttinen), the book that the child has chosen for their bedtime story does everything in its power to prevent the adult from reading it. For example, the book turns into a steering wheel, adds words into the text, and changes fonts suddenly.

Princess stories and folk tradition

Story traditions and fairy tales are living, thriving, and finding new forms in children’s literature. Fantasy literature also uses elements of folk tradition.

Nollis: maailman ainoa nollasarvinen by Tuomas Marjamäki and Antti Nikunen (WSOY) follows a hornless unicorn and a zebra without stripes. The creatures live on a farm in Pönttölä and their foolish activities are tied to traditions of both beast fables and the Finnish fools of blason populaire genre. Tales of modern fools are also told in Hemmo ja hölmöläiset written by Pamela Mandart and illustrated by Estonian Anders Varustin (Basam books).

Prinsessa Pikkiriikin hiukkasen hurjat sadut by Hannele Lampela (Otava, ill. Ninka Reittu) features familiar fairy tales told from new perspectives. The three bears have a visitor, who wants to touch people’s things in their home without permission, and a fairy never gets invited to a birthday party. The princess tradition also finds new forms in Prinsessa joka lähti kälppimään, a picture book by Saara Kekäläinen and Netta Lehtola (S&S). Leona is a princess, who doesn’t want to sit around waiting for a prince, and decides to go on her own adventure, on which she meets many things familiar from fairy tales. In Pikkuhiiren satulipas by Riikka Jäntti (Tammi) a mother mouse tells mousified versions of fairy tales. Tuhkimon eeppinen hups, a children’s novel by Jussi Lehmusvesi (Otava, ill. Christer Nuutinen) also sees the main characters have an adventure in a fairy tale world. Ariana and her friends have been placed into the story of Cinderella, and they have to help the story to get its happy ending.

A fairy tale collection Satumaa kuuluu kaikille (WSOY, tr. Saarni Laitinen) features 17 stories and is translated from Hungarian. The collection was edited by Boldizsár M. Nagy and illustrated by Lilla Böleczk, and it is meant to show that fairy tales belong to everyone regardless of gender, looks, sexual orientation or socioeconomic class. There are both original stories and new versions of classics in the collection, and they feature a cast of characters that are diverse and challenge the idea of what a hero can be.

Various creatures and characters from folk traditions are featured in children’s books. Karmeat satuolennot, a non-fiction book by Vuokko Hurme (WSOY, ill. Julia Savtchenko), was published in Tietopalat series, and it presents familiar monsters and fairy tale creatures. House elves are the main characters in two books: the fantasy novel Jakov Korina ja synkiön salaisuus by Helena Immonen (Kumma), and Kaiho-kotitonttu ja rauhaton rantaloma, the second installment in the Kaiho-kotitonttu series by Emilia Aakko (Kumma, ill. Veera Aro).

The Pax series by Åsa Larsson and Ingela Korsell is inspired by the Nordic folk traditions. Two books were published in the series in Finnish in 2022, the fourth and fifth installments, namely Para and Kummitus (Otava, ill. Henrik Jonsson). They feature for example a para, a witch’s helper that steals for the witch. Nordic magic and mythology are also featured in the Pohjantuli comic series by Malin Falch, which also had two books published, namely Viikingit ja Varis and Lintusisaret (Story House Egmont, tr. Jonna Joskitt-Pöyry, original Nordlys).

Elements of Finnish mythology can be found in Laakson linnut, Aavan laulut, a youth novel by Katri Kauppinen (Otava). The poetic story features a fight between two towns, and a young girl Pihla, who is learning healing magic.

The classic Finnish fairy tale Merenkuningatar ja hänen poikansa by Anni Swan was republished as a picture book with new illustrations by Mari-Annikki Serdijn and retold in modernized language by Anna Pölkki (Kangasniemen kirjasto).

Growing horror

Horror is a popular genre among both children and the youth, and there is a lot of horror literature published for different age groups. Suomen lasten kummituskirja by Raili Mikkanen (Minerva, ill. Sirkku Linnea) is a collection of ghost stories from all over Finland.

Marko Hautala is known as a horror author, and his second children’s book Lauri Luu ja kirjaston muumio (Haamu, ill. Broci) features a mummy, who escapes from a history book filled with incorrect information, and starts wreaking havoc in a library. In Kirjaston kiusanhenki, the first installment in the Mysteerjengi series by Juha-Pekka Koskinen (Karisto, ill. Saana Nyqvist) there is a ghost hunt in the Rikhardinkatu Library.

Horror books for children were published both in ongoing series, and starting new series. The Iik series by Anu Holopainen got its seventh and eighth parts, Räyhähenki and Krampus (Myllylahti). Hereiset series by Siri Kolu was kicked off with the first book Yön salaisuus (Otava, ill. Johanna Lumme), in which the main character Leo learns that every night his parents fight against nightmare creatures. Two books were also published in Varjot series by Timo Parvela and Pasi Pitkänen: Krampus and Auroria (Tammi). In the series the main characters have to fight the shadowless in a world inhabited by elves and other creatures inspired by Nordic folk traditions.

Elokuussa minä kuolen, a youth novel by Anne Leinonen (Haamu), follows Alma, who has been gifted a cursed pearl necklace, which will cause Alma to die at the end of the summer. A gravely ill girl moves next door, and she shows Alma a path to another world, where she has to face both her own fears and a monster.

Kalmanperho, the first novel by Ulpu-Maria Lehtinen (S&S) is a fantasy book with horror elements. Following a butterfly, Lilja ends up in a parallel world, a town called Kalmanperho, that is threatened by darkness. Sysi, by Sini Helminen (Myllylahti) is a new part in the Lujaverinen trilogy, a mix of fantasy and horror, in which students of art theory meet the dead.

There were three books published in the horror novel series by A. R. S. Horkka: Kellopelikuiskaaja, Korvaaja and Jäätävää (Tammi). Kellopelikuiskaaja takes place in an apocalyptic Helsinki tormented by a plague. In Korvaaja the main character Taika has a mysterious connection with people who have died at Raaseporinjoki.

Forest, nature, and environmental protection

Forest is present in books both as a mythical setting, and as something to be protected. In Kärsimyskukkauuteaddiktio, a youth novel by Oona Pohjolainen and Adile Sevimli (Otava), forest is a scary place for regular people, because it is where witches draw their power from. When Juno moves to a city, she meets other witches and understands that logging and demolishing parks is diminishing their living spaces.

In Metsämuistikirja by Johanna Venho and Sanna Pelliccioni (Teos) Kaarna wants to fight against the plans of logging in her near forest. Logging also causes confusion in Mur, mitä tuuli toi by Kaisa Happonen and Anne Vasko (Tammi). Mur the bear smells something new and strange, and following its nose it finds the logging site.

Themes of environmental protection and biodiversity have been important in recent years, and they come up in many books again. Kiivetään puuhun: matkataan kasvien kanssa, a non-fiction book for small children by Laura Ertimo (Karisto, ill. Sanna Pelliccioni) explains how plants and animals cooperate in the nature.

In Operaatio ilmastoareena by Päivi Tuulikki Koskela (Atrain & Nord, ill. Hanna Kenakkala) kids uncover a greenwashing conspiracy, when they find out that an energy company that advertises wind energy actually uses coal. In Raakku Raakile by Seija Helander (Enostone, ill. Anne Stolt) a crow asks for help from a little boy, Kuutti, who likes endangered animals. The crow comes from a research field plant in Konnevesi, where a small freshwater pearl mussel is in need of help.

In Pouke ja meren pauhu, a picture book by Eveliina Muotkavaara (Mini), Pouke is cleaning up the trash from the seashore with their mother and waiting for the sea to freeze. The illustrations in the book are made using embroidery and recycled fabrics.

Kestokamut järkieväiden jäljillä by Maijaliisa Erkkoa and Riikka Pajunlahti (Gaudeamus) is a non-fiction picture book with a story about children, who go on a summer camp on a farm. The book explains where food comes from, how recycling works, and guides towards more environmentally friendly choices.

Harmaja luode seitsemän, a youth novel by Leena Paasio (WSOY) follows Eetu, who dives on his free time and tries to find out what happened to his mother, who disappeared on a swimming trip. Other parties seem to be interested in the documents left behind by the mother who was an environmental researcher, and Eetu notices something strange going on with a company selling clean boat paints.

Another book seeking to promote environmental awareness is the picture book published by the grocery store chain Lidl; Luka ja kummallinen kauppareissu created by Hanna-Mari Engblom and Reettamaria Mynttinen. In the book Luka does groceries with his mother, who tells him about accountability and environmentally friendly choices.

*****

Kirjakori by the Finnish Institute for Children’s Literature showcases the entire scope of childrens and youth literature in 2022. Kirjakori statistics have been recorded since 2001. The statistics and the report are based on the books that can be found in the collection of the Institute’s Library. The titles have been donated to the library by publishers.

Translation: Iiris Kettunen